Roast Magazine’s Daily Coffee News rans a story claiming climate change was causing “ongoing systemic shocks,” harming coffee production by creating more simultaneous extreme weather events across different growing regions. This is false. Data refutes claims that extreme weather events are increasing in number, intensity, or frequency. Also, coffee production is increasing amid modest warming.

According to the Roast Magazine story, titled “Study: Climate Change Increasing ‘Systemic Shocks’ to Coffee Production:”

The global coffee industry can expect increasing and “ongoing systemic shocks” to coffee production due to climate change, according to new research published this month in the journal PLOS Climate.

The research, which was funded by the Australia’s national Climate Service agency, says that there has been a been a notable increase in “synchronous climate hazards” among the world’s 12 largest coffee-growing countries over the 40 years ending in 2020. In other words, more coffee-producing areas are being negatively affected by climate change at the same time.

The study takes particular note of the El Niño, the La Niña and the Madden–Julian oscillation (MJO) climate phenomena effecting global tropical regions throughout the coffee-growing world.

There are so many false or mistaken claims packed into these three introductory paragraphs its hard to know where to begin to refute them. Starting with the last paragraph first. El Niño, the La Niña and the Madden–Julian oscillation are large scale natural oceanic and atmospheric circulation patterns and they do effect climate on regional and trans- and multicontinental scales. However, contrary to the implication of the paragraph and evidently the study it references, those patterns drive weather events. Climate models are unable to account for the impacts of these patterns on climate change.

Data neither show, nor does the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report, any significant changes in these large-scale natural circulation patterns that can be linked to climate change. There is no evidence whatsoever that climate change is altering these natural patterns; either making their impacts more severe or the circulation patterns themselves more persistent or erratic. Whatever effect El Niño, the La Niña and the Madden–Julian oscillation, or other large scale short- and long-term natural oceanic and atmospheric patterns, might be having on coffee production, they have always had such effects—there is no evidence this has changed.

Just as there has been no detectable change in various periodic oceanic and atmospheric patterns that are drivers of weather, there has also been no increase in the number or severity of various extreme weather events which effect coffee growing regions, as well as the rest of the world. As discussed at Climate at a Glance, data does not show droughts, floods, hurricanes, or other classifications of extreme weather events that might negatively effect coffee production are increasing in number or severity globally. And higher carbon dioxide concentrations and the decline in unseasonable cold spells have benefited coffee production, as they have almost every other crop.

Which leads us to the most important claim made in the paper. Because oceanic and atmospheric circulation patterns aren’t changing, and weather isn’t becoming more extreme in any way that has been measured, is it impossible for these factors to be causing a decline in coffee production. Indeed, data from the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) shows that it is not.

“The occurrence of these spatially compounding events has become particularly acute over the past decade, with five of the six most hazardous years occurring since 2010,” say the authors of the study cited as evidence of a pending coffee apocalypse in Roast Magazine. Such struggles are not evident in the production data recorded by the FAO.

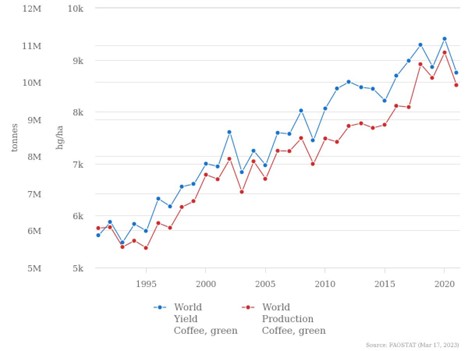

FAO data show that coffee yields set new production records seven times since 2010, most recently in 2020. And at no time after 2010 did coffee yields fall below yields recorded before 2010. Indeed, from 1990 to 2021, the last year for which data is currently available, during the recent period of climate change, coffee yields increased by nearly 56 percent.

What’s true of coffee yields is also true of coffee production. Even as a growing number of coffee producers have begun growing boutique coffee varieties using only organic methods, which have reduced yields on those plantations, coffee production overall has grown substantially. Once again, the data show that rather than the period since 2010 being one of hard times for coffee producers, production has set records regularly. Between 2010 and 2021, coffee set records for production five times, and coffee production has grown by nearly 17 percent during that period. Over the term which climate change is measured, 30 years, coffee production has increased approximately 64 percent. (See the figure, below)

To sum up: Roast Magazine claimed climate change was altering large scale oceanic and atmospheric circulation patterns, which was causing an increase in the number and severity of simultaneous extreme weather events, allegedly threatening coffee production worldwide. Each of these claims is refuted by hard evidence. Perhaps going forward, rather than uncritically parroting the alarming findings from the most recent, but untested, study asserting climate change threatens a serious coffee decline, the reporters at Roast Magazine will look into the data and ask some hard questions to determine whether setting off the climate alarm is justified. If they do so, they will likely find they can sit back, relax, and enjoy their next cup of Joe, unburdened by fears that this enjoyable daily ritual will soon pass.