A recent article on World-Grain.com (World Grain‘s online publication) says Indian crops like rice, corn, and wheat, are being forced to adapt to climate change. This claim is a strange because weather patterns in India haven’t worsened significantly during the recent period of modest warming, and the crops discussed have all increased dramatically over the same time period. Data indicate harvests are not being negatively impacted by stronger or weaker monsoon seasons, or other weather events.

The article “Study: Indian crops adapt differently to climate change,” reports that the International Food Policy Research Institute’s (IFPRI) recent Global Food Policy 2022 report claims “climate change may push 90 million Indians toward hunger by 2030 because of a decline in agricultural production and disruption in the food supply chain.”

Supply chain issues, geopolitics, and weather are unpredictable, yet Indian agricultural production trends over the past decades of global warming show a relatively steady increase in the major crops examined. Climate Realism has discussed Indian weather and food production, here, here, and here, as a sample, indicating that India’s weather has not become more extreme or unpredictable, and its crops are doing well. Nothing has changed since these documents were posted.

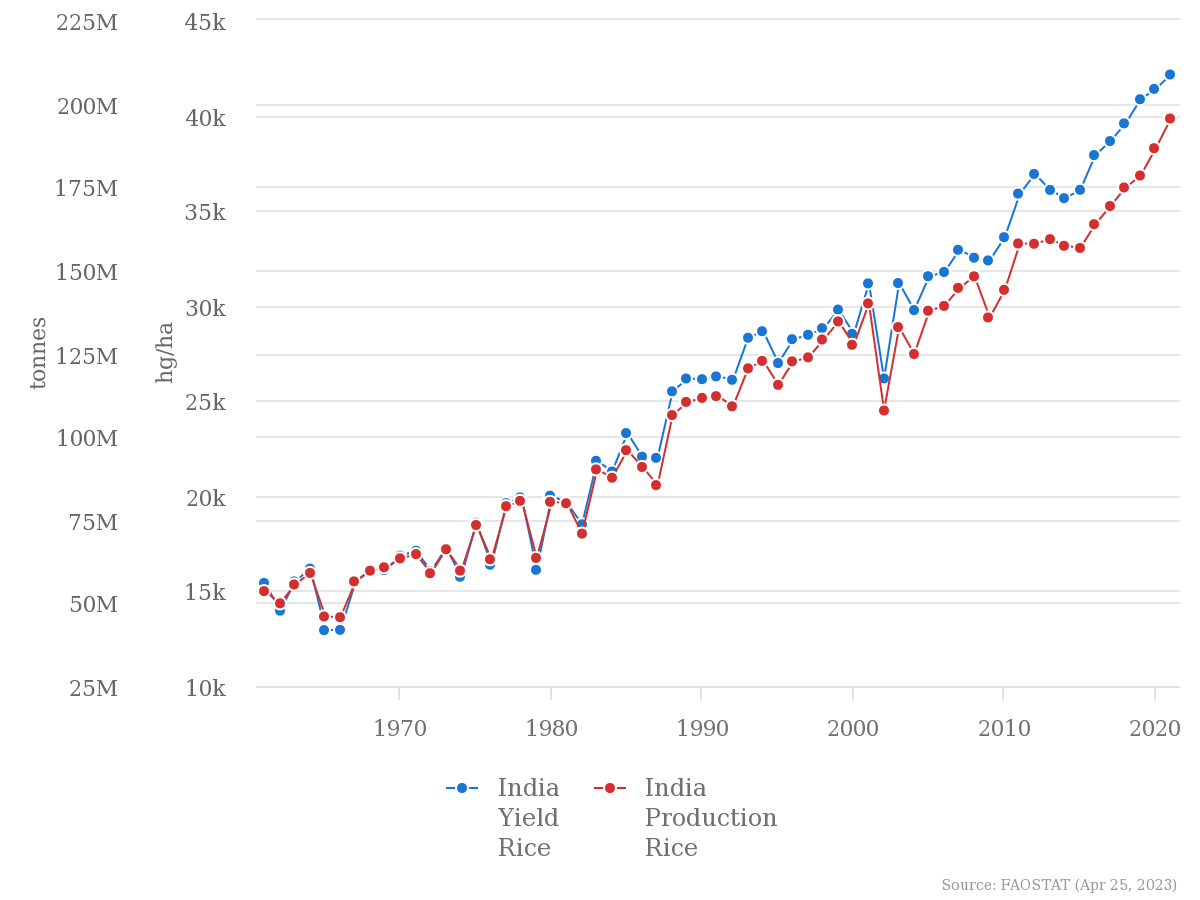

Rice, a major staple food crop for India, has seen a nearly unbroken increase in production and yield since the 1960s. Indian rice production skyrocketed 265 percent, with recent years actually seeing an increase in the slope of production gains. (See figure 1 below)

This is despite, and possibly because of, the fact that average global temperatures and CO2 emissions have risen during the same time frame. The growth in CO2 has enhanced crop growth and improved plants’ water use efficiency.

The World Grain article covers a study done by researchers at the University of Illinois which looked at 60 years of crop data in India, focusing on rice, corn, and wheat. They found “farmers have been able to adapt to temperature changes for their corn and rice crops but not for wheat.”

This is an odd claim, because production and yield data for all three crops show dramatic growth during the period of modest warming. Naturally farmers in different parts of India adapt to different weather events and trends differently, depending on the kind of crop being grown.

The article reports that highly productive farming regions that use modern industrial farming techniques are less impacted by short term weather events, or the fluctuations of monsoon season, than less developed areas. World Grain reports that the researchers say, “there are two ways by which the crops can adapt: the farmers can change their management practices or switch to varieties that are more resilient.”

Again, this seems obvious.

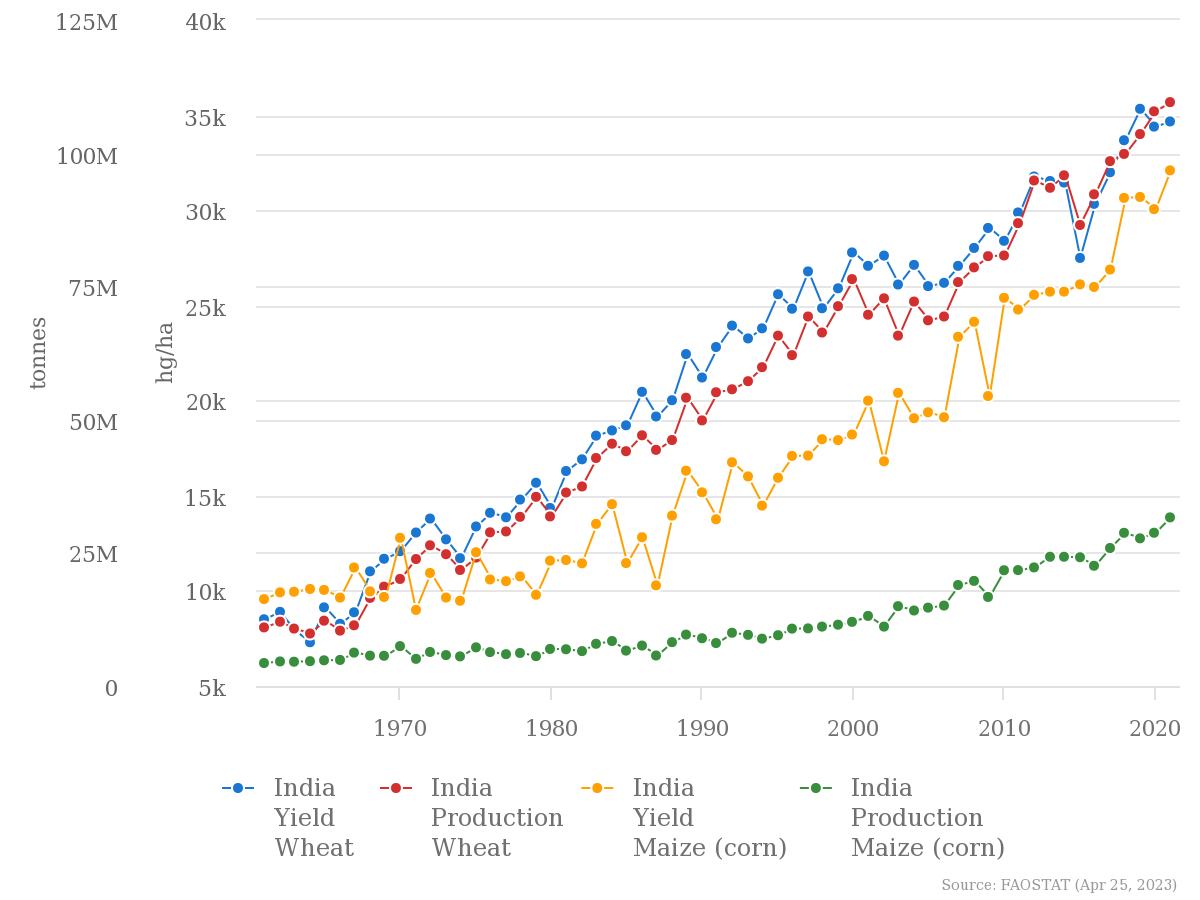

Looking at the overall trends, between 1960 and 2021, the same time-period covered by the study, corn and wheat, the two crops besides rice discussed in the article, production and yield data show dramatic increases for both:

- Corn production has risen 235 percent;

- Corn yields have increased 633 percent;

- Wheat production has increased 896 percent;

- Wheat yields have increased 307 percent. (See Figure 2 below)

The hypothesis that these trends will suddenly reverse in the next seven years is completely unjustified.

Of particular note is the fact that the study suggests wheat farmers have been unable to adapt to a changing climate, yet production and yield data on wheat indicates that, adaptation or not, wheat farmers are doing just fine.

For as long as agriculture has existed, farmers have had to adapt to changing weather and climate conditions. The increasing yields and production for major crops in India refute any claim that climate change is having a net-negative impact on Indian agriculture.

India is a large country, containing a number of different biomes, each with their own regional climates from tundra to tropical rain forest. Some ecosystems are and will continue to be more suitable for certain crops than others, and farmers should be expected to adapt their planting to those conditions.

World Grain should have fact checked the IFPRI’s 2022 food policy report before uncritically parroting its easily falsified claims. If it had, it could have delivered justified good news about Indian agriculture, rather than generating unreasonable fear about climate change’s impacts on farm prospects in the country.