Guest Post by Cliff Mass

Editor’s Note: In the run up to and aftermath of the recent “bomb cyclone” and atmospheric river that slammed the Pacific Northwest, bringing high winds, rain, and snow, many in the media, for example, Phys.org and the University of Miami News, have tried to connect that storm and similar storms in recent years, to climate change, claiming climate change is making them more frequent or powerful. This is false. Heartland Senior Fellow, award winning meteorologist, Anthony Watts has debunked such claims in the past, both at his popular climate website, Watts Up With That and at Climate at a Glance. Bomb cyclones have been experienced and known throughout history, although they were only labeled as such in the 19th century.

In the guest essay below, by atmospheric scientist and science blogger, Cliff Mass, a fellow of the American Meteorological Society and professor of Atmospheric Sciences at the University of Washington, explains that when the press has reached out to him for comments about the recent extreme weather event, he refuted claims that bomb cyclones and atmospheric rivers have become either more frequent or more powerful. The data just doesn’t support such claims.

Are Eastern Pacific Cyclones Become More Frequent or Stronger?

During the past three days, I have received several calls from media folks asking the same question:

Are storms like this week’s “bomb” cyclone becoming stronger or more frequent due to global warming?

If not, will global warming cause such increases in the future?

The answer to these questions is quite clear: NO.

There is convincing scientific evidence that our region has not seen an increase in such storms and that a warming planet will not bring more meteorological “bombs” into our region.

First Some Terminology:

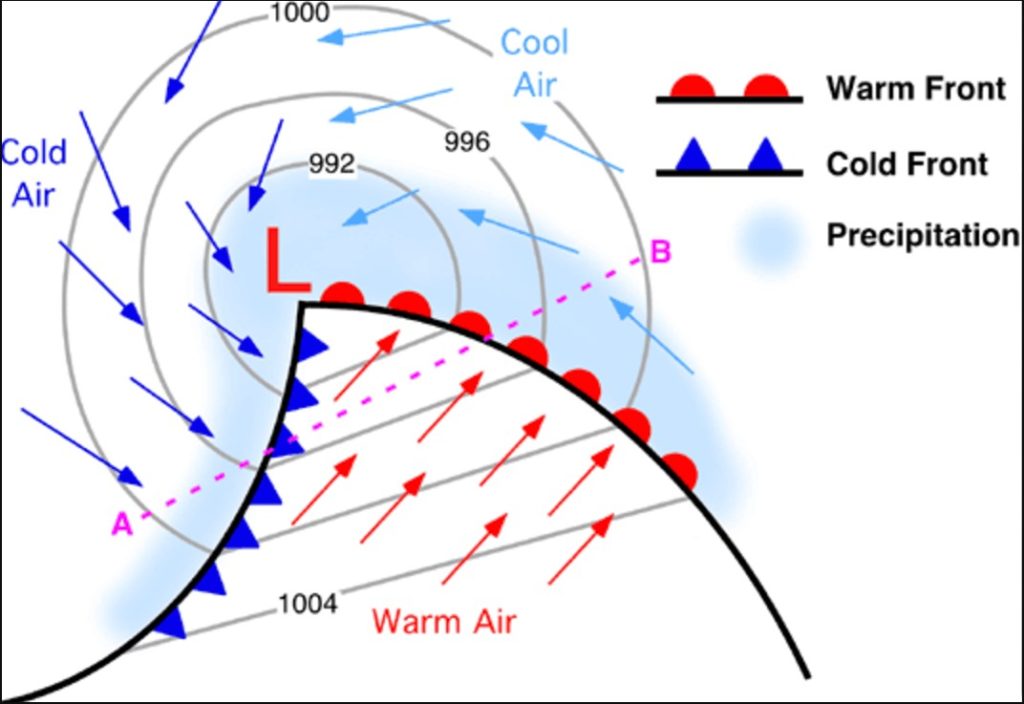

A midlatitude (or extratropical) cyclone is a low-pressure center with winds rotating counterclockwise around it in the northern hemisphere. The strength of the cyclone is generally quantified by the central pressure, although size is also important. Generally, the lower the central pressure, the stronger the cyclone and the more powerful the winds.

As shown by the figure below, cyclones generally form in regions of strong horizontal temperature change….in fact, such temperature contrasts are the fuel of such storms.

Regarding central pressures, garden variety storms in our region have pressures around 990-1000 hPa. Strong storms perhaps 980-990 hPa, and powerful cyclones have pressures of t965-980 hPa, with extreme storms even less.

Tuesday’s storm dropped to an astounding 943 hPa, tying the record for the past 70 years.

Cyclones that rev up particularly rapidly are called “bombs”…..and the media has certainly fallen in love with this term. By definition, bomb cyclones deepen by 24 hPa or more in 24 h. This definition is completely arbitrary. Really just for fun.

Are Local Cyclones Getting Stronger?

The answer is clearly no. There has been no increase in the frequency or intensity of landfilling or near-shore cyclones in our region.

Most of the famous local cyclones occurred during the early to mid-20th century, with the last major landfalling cyclone in 2006 (the Chanukah Eve Storm).

Another way to demonstrate the lack of increase in storms is to plot sea level pressure over time at a point on the Washington Coast (Ocean Shores). As shown below, there is no evidence for an increase in the lowest pressures (say below 980 hPa).

Will Global Warming Increase Strong Windstorms Over the Region?

A group of us at the UW (in association with the UW Climate Impacts Group) did a formal study of this question, funded by Seattle City Light.

We made use of a state-of-science regional climate model driven by an ensemble of Global Climate Models.

This research did not find an increase in extreme winds over the region (we examined several locations). A graphic from the analysis of the extreme wind trends through the end of the century is shown below.

There are good scientific reasons to expect little change in the intensity of midlatitude cyclones over our region.

For example, global warming preferentially warms the Arctic in the lower atmosphere, thus weakening the north-south temperature difference that drives the storms. On the other hand, the temperature change is strengthened aloft, with the result being a wash for the storms.

In summary, natural variability and processes sometimes can come together to produce very intense cyclones like the one we experienced on Tuesday.

We experienced a rare, extreme event and there is no reason to expect that such storms will become more frequent as the planet slowly warms.

Originally posted at Cliff Mass Weather Blog, reposted with permission.