By Linnea Lueken and H. Sterling Burnett

A recent article at The Independent, “How the climate crisis will push up prices for your Easter chocolate,” claims that cocoa bean production is threatened by climate change, and this is why prices are increasing. This is false. The Independent cites a study using a novel, recently developed AI model forecasting cocoa production in various countries, rather than investigating the full picture, and real world data, including neighboring nations’ cocoa production. To the extent cocoa prices are rising, it is not due to climate change induced shortages but rather government policies.

The Independent claims that extreme heat is increasing the risk to crops, and has been for “the past two decades in Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Ecuador, and Indonesia, according to modelling shared exclusively with The Independent from ClimateAi, a California-based machine learning company that models harvest outcomes. And that impact is only set to get worse as global temperatures increase.”

This AI modelling “has only been around for the last few months, and has been specifically designed to create accurate outlooks for more data-scarce environments like Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire[.]” The company claims it incorporates historic weather data, current satellite data, soil information and topography, as well as “local agricultural knowledge[.]”

They use the model outputs to declare that yields and production of cocoa are declining because of climate change, or at the very least are “at risk” of declining. It is too bad that the models were shared exclusively with The Independent, and the company’s work is proprietary, because it makes it impossible to know whether or not they are leaning on the same flawed climate models that consistently mislead on agricultural production – as Climate Realism has pointed out many times for crops around the world.

Tellingly, since the models are new and propriety, their results lack transparency, and there is no suggestion that the models have been peer reviewed or verified by testing by outside researchers. The company behind the proprietary AI modelling is basically asking the world to trust its findings, take it on blind faith – that’s not how science works.

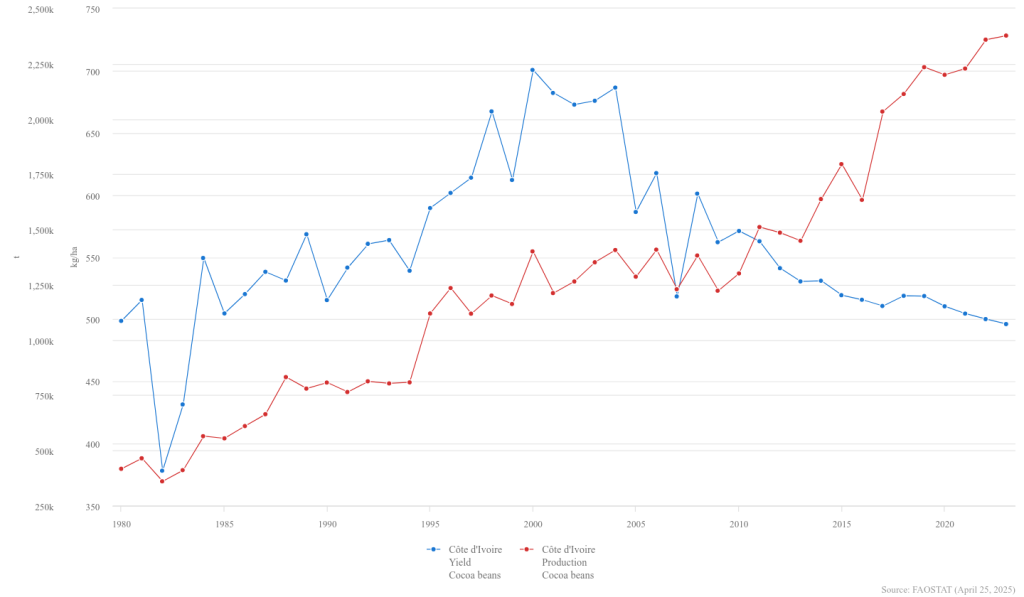

Real world data, as opposed to unverified model outputs, by contrast show that, in general, cocoa yields and production have increased during the recent period of slight warming. Interestingly, data show that while yields from cocoa plantations in Côte d’Ivoire are declining, production has increased considerably during the recent period of modest warming, according to UN Food and Agriculture Organization (UN FAO) data. (See figure below)

The Independent only acknowledges the declining yields, but neglects to mention that total production from the country hit an all-time record high in 2023. Production has increased 469 percent since 1980.

This indicates that the amount of cocoa from individual farms may be declining, likely older farms but more are coming online.

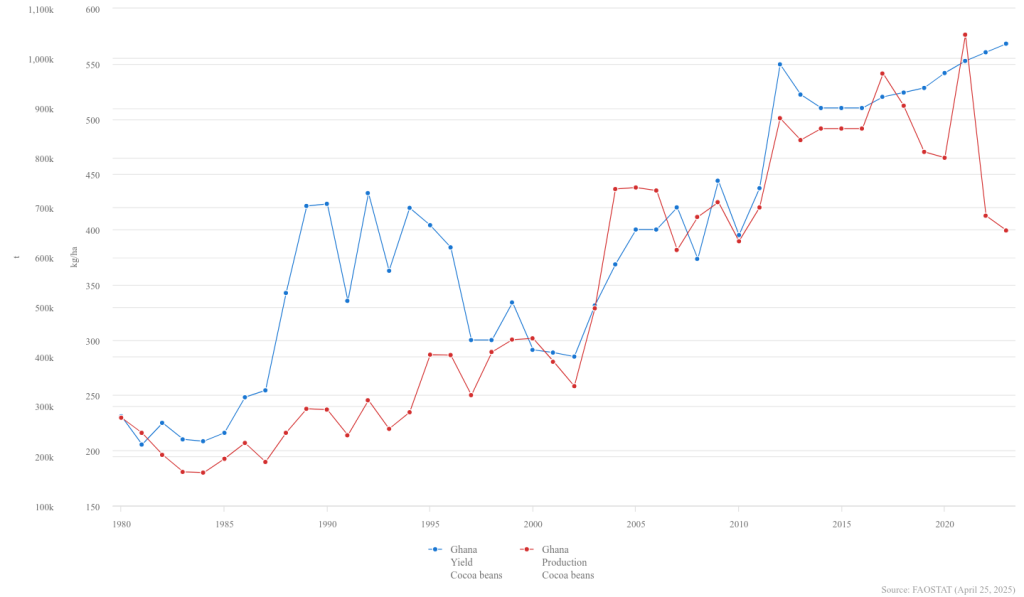

If climate change were the reason behind Côte d’Ivoire’s woes, it would be expected production on farms in nearby countries would suffer similarly, since weather is widespread. Yet Ghana’s yields levels have not experienced the declines Côte d’Ivoire has. (See figure below)

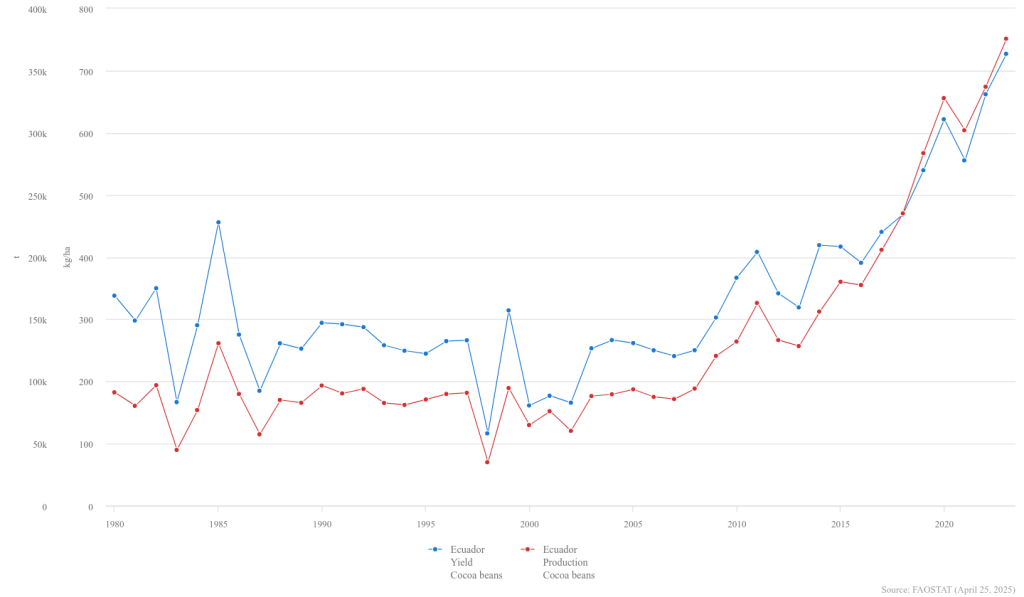

Another country evaluated as threatened by the AI study is Ecuador. UN FAO data show that they have had consistent production and yield records; since just 2015, Ecuador’s cocoa production and yields have broken previous records six times. (See figure below)

So what is it that is making Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire cocoa production suffer, leading to such high cocoa prices? The answer can be found towards the end of The Independent’s article where it mentions the fact that Ghana’s government has a stranglehold on cocoa pricing, noting that last year, “the Ghana Cocoa Board (COCOBOD), which controls salaries for the country’s cocoa farmers, announced that it would raise the amount it pays cocoa farmers by 45 per cent[.]”

Blogger Jo Nova has a writeup on this that is devastating to the alarmist narrative. She points out that the price fixing in Ghana, which is the second largest cocoa producer in the world, is a major driver for the issues that led to spikes in prices the last year:

African governments have fixed the price of cocoa for decades, forcing poor farmers to work for a pittance, and keeping the big profits for themselves. Not surprisingly, even though there is a wild price spike, farmers in Ghana are leaving the industry, smuggling crops out (because they get a better price). They didn’t plant new trees, they ran out of money for fertilizer, and didn’t try new varieties. Their children don’t want to farm cocoa, and the yields are falling on old sickly plantations.

So, surprise, socialist government controls wrecked the industry and they are now scrambling to put the pieces back together. Things are so desperate, the government of Ghana raised the price of cocoa by 58% last April and then raised the price of cocoa by another 45% last September, to try to reduce the smuggling. (The government was losing too much money). At one point last year it was estimated that a third of the national crop was lost to smugglers. A few months after this, the farmers were hoarding their beans in expectation the government would have to give them another price rise. Just chaos for everyone.

The Independent fails to discuss smuggling at all.

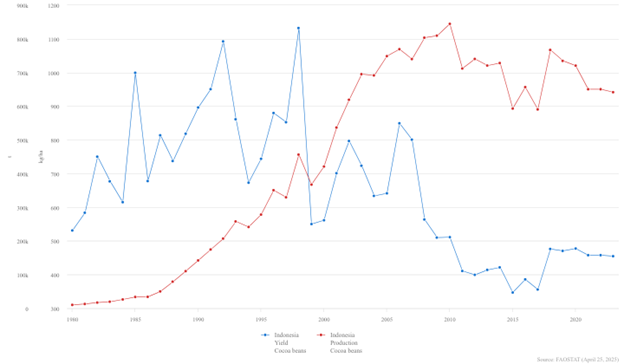

A similar result is found in Indonesia. After the Indonesian government embraced various U.N. climate and sustainable development goals, and began reaping the international aid that accompanied adoption, it began encouraging its farmers to adopt “sustainable” practices, including reducing the use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides, and focus on the “quality” of the cocoa produced over the quantity. The result: after a sustained growth in production from the 1980s through the early 2000s, yields began to decline, with production falling shortly thereafter.

After initially falling, Cocoa production has now basically flatlined in Indonesia since the country signed the Indonesia Compact in 2013 with a focus on improving cocoa quality, natural resource use, and lowering greenhouse gas emissions. After 2018, the program ended and the money ran out. The damage was done, cocoa production and yields have never recovered to pre-Compact levels. (see the figure, below)

Crop production will always have good and bad years in different parts of the world, especially in places with government meddling and mishandling of resources and price fixing which makes it harder for farmers to invest in new cocoa plants when others are growing old, the soils and trees worn out, making them less able to withstand bad weather seasons. Blaming climate change in an effort to rally support for green policies is misleading by the omission of other relevant factors, and is counterproductive to improving cocoa yields and production.

Another case of misleading the public with uncorroborated data that could easily be skewed and scurrilous data that projects the worst possible outcome! If this was so important why would they not express the results in easily accessible format than behind some AI generated algorithm that could easily be biased! GIGO!