The New York Times (NYT) claims in its recent article, by Rebecca Dzombak, “It’s Not Just Poor Rains Causing Drought. The Atmosphere Is ‘Thirstier,’” that global warming is intensifying droughts by creating a “thirstier atmosphere” that sucks more moisture from the land. This assertion is false, clearly debunked by real-world data. The idea that a warming atmosphere is increasingly “demanding” water anthropomorphizes a complex physical process, and worse, ignores major natural variables—like volcanic activity and regional climate drivers—that actually influence drought more directly. Evidence suggests there is a record amount of water vapor in the atmosphere now, that droughts are regional, not global, and that “atmospheric thirst” is more rhetorical flourish than scientific fact.

Let’s begin with semantics. The atmosphere is not a sentient entity—it doesn’t get “thirstier.” That is a term more appropriate for a Gatorade commercial than climate science. What the researchers are referring to is an increase in potential evapotranspiration, a concept that has been well known for decades. Higher temperatures can increase the potential for evaporation—but that doesn’t mean evaporation always increases. Factors like humidity, cloud cover, soil moisture, ground cover, and wind speed all play major roles, and those often vary independently of global temperature.

Even more crucially, this narrative conveniently omits one of the most significant injections of water vapor into the atmosphere in recent history: the eruption of the Hunga Tonga–Hunga Haʻapai volcano in January 2022. According to a 2022 study published in Geophysical Research Letters, the eruption blasted approximately 146 teragrams (146 million metric tons) of water vapor into the stratosphere—enough to increase global stratospheric water vapor by 10%. It documented a massive, unprecedented increase in stratospheric water vapor from a natural volcanic event—an event that should absolutely be part of any honest discussion about current atmospheric moisture and so-called “thirstier” drought models.

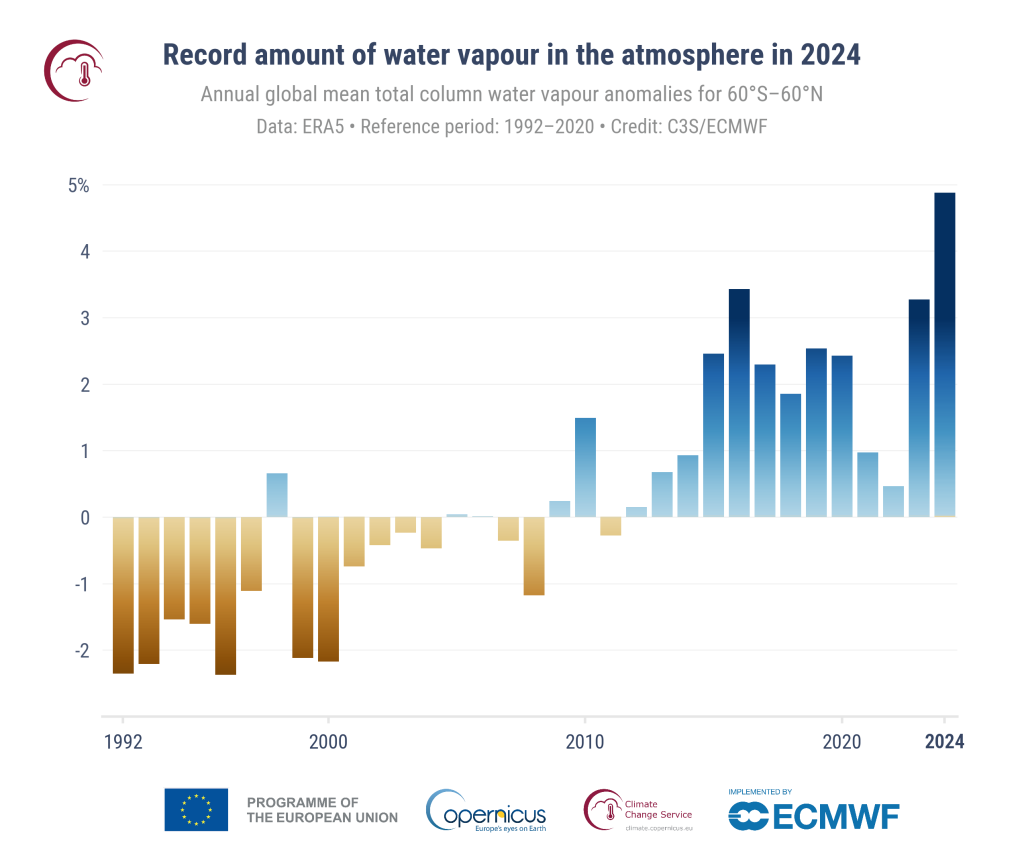

That Hunga Tonga’s injection of water vapor clearly shows up in the data from Copernicus as seen in the figure below:

That’s not a minor blip, and it blows the NYT idea of a “thirstier” atmosphere clear out of the water. Water vapor is the most potent greenhouse gas, and this sudden influx significantly influences short-term atmospheric dynamics, including regional precipitation patterns and, yes, drought. Funny how the NYY fails to mention this natural event that throws a wrench in their narrative.

What’s more, the NYT article leans heavily on a model-based study that attempts to back-calculate “atmospheric thirst” going back to 1901. But here’s the catch: models are only as good as the assumptions and data you feed into them. The International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Sixth Assessment Report (AR6), Chapter 12, clearly states that “there is low confidence in the human influence on observed changes in meteorological droughts globally” (IPCC AR6 Chapter 12, Section 12.3.2). The IPCC—the supposed gold standard of climate consensus—explicitly distances itself from attributing droughts to human-caused climate change. Yet the NYT conveniently skips that detail.

Rather than climate change causing a long-term trend of increasing droughts, the IPCC also reports with “high confidence” that precipitation has increased over mid-latitude land areas of the Northern Hemisphere (including the United States) during the past 70 years, and the agency expresses “low confidence” about any negative trends globally. So the “thirstier” climate is dropping more precipitation back to Earth, resulting in less “thirsty” soil. You can’t have it both ways, if the Earth is getting more rain, it can’t be drying out – and years of drought data show that it is not.

Drought is a regional phenomenon driven by local weather patterns, ocean currents like ENSO (El Niño–Southern Oscillation), and natural variability, not some imaginary global “drought machine.” As the Climate at a Glance summary from The Heartland Institute points out, data from the U.S. and global sources do not support the claim that droughts are becoming historically unprecedented. In fact, one peer-reviewed study found that the most intense global droughts of the last 120 years occurred in the early to mid-20th century, long before the recent increase in CO₂ emissions.

Although the NYT article that there has been a 74 percent increase in drought-affected area between 2018 and 2022, even if true, the statistic is nothing more than a a short-term snapshot influenced by factors like La Niña events, reduced solar activity, and, again, the Tonga eruption. Cherry-picking short timescales is a hallmark of climate alarmism. If they’d extended the dataset to include the Dust Bowl of the 1930s or severe droughts in the 1950s, or even data over the past 30 years, no increasing trend of areas affected by drought would show in the data.

The NYT also assumes that the purported increase in atmospheric water vapor will broadly negatively impact human life. But higher carbon dioxide concentrations and modest warming have resulted in longer growing seasons and enhanced carbon dioxide fertilization, which has dramatically boosted crop yields and improved drought resilience in crops. Any anthropogenic increase in water demand is not due to climate change, but population growth, accompanied by increased agricultural and urban water use. Rising water demand can be met by adaptation—not hysteria. As the NYT article mentions, some farmers are updating irrigation systems. That’s good. But blaming the need for irrigation upgrades on climate change is like blaming a new set of tires on the existence of roads.

Lastly, we’re told that “the trend is set to continue”—again based on model projections, that are untested and not based on observed trends. But history has shown us that nature often defies the climate models. In the early 2000s, scientists predicted permanent drought (so-called “climate aridification”) in California, only for the state to swing to record-breaking wet years just a decade later. Nature is variable, not linear.

In conclusion, the NYT article is a masterclass example of turning natural variability and questionable modeling into a headline-ready climate crisis story. By attributing regional droughts to global temperature trends and anthropomorphizing the atmosphere as “thirsty,” they abandon scientific rigor in favor of sensational storytelling. Compounding their error, the NYT ignores countervailing data on rainfall, long-term drought, and even the IPCC’s own cautious language on drought attribution.

When news outlets resort to metaphors about “thirsty skies” and glaringly omit factual explanations, they’re not informing—they’re indoctrinating. Honest climate reporting, requires a lot less narrative and a lot more reference to the hallmarks of the scientific method: available data and testable propositions.