In The New York Times’ (NYT) op-ed, “Turns Out Air Pollution Was Good for Something,” Zeke Hausfather and David Keith argue that because sulfur particles from past industrial pollution once cooled the planet by reflecting sunlight, policymakers should now consider a deliberate version of that process. They suggest aircraft could inject sulfur into the upper atmosphere to mimic the cooling once provided by dirty smokestacks, pointing to volcanic eruptions such as Mount Pinatubo in 1991 as evidence the method would work. This idea is wrong-headed madness. Experience demonstrates geo-engineering ideas such as this have dangerous and unpredictable consequences.

The authors write that “geoengineering the climate in this way is not a new idea,” and claim that “a more modest approach” of maintaining present temperatures with controlled sulfur injections buying the world time for carbon dioxide reductions to continue.

But geoengineering by blocking the sun is a dangerous fool’s errand. First, the potential unintended consequences are enormous and unpredictable. Sulfur dioxide particles injected into the upper atmosphere would scatter sunlight differently depending on latitude. At middle to low latitudes, sunlight passes through less atmosphere, so scattering effects are modest. But at higher latitudes, sunlight travels through more atmosphere, amplifying scattering—just as sunsets turn red because of the increased distance light travels through more air and particles at low sun angles. Injecting reflective particles globally would therefore not create uniform cooling. It would over-cool the polar and sub-polar regions, while perhaps under-cooling equatorial areas. The result would be an uneven, artificial climate system with consequences no climate model can reliably predict.

These regional impacts would not just be academic. Farmers in Canada or Scandinavia might see shortened growing seasons. Populations in northern Russia could face colder winters. Developing nations in Africa or Asia could sue over disrupted rainfall patterns or crop failures. Geoengineering would open a legal and geopolitical Pandora’s box of claims, counterclaims, and lawsuits, as countries argue that someone else’s climate tinkering damaged their own livelihoods. Even Hausfather and Keith concede in their NYT op-ed that large-scale deployment “could exacerbate climate change in some locations, perhaps by shifting rainfall patterns.”

Aside from these uncertain consequences, one consequence of this scheme is certain, increased sulfur pollution, most likely resulting in acid rain which changes the pH of waters and damages buildings, statues, and other structures.

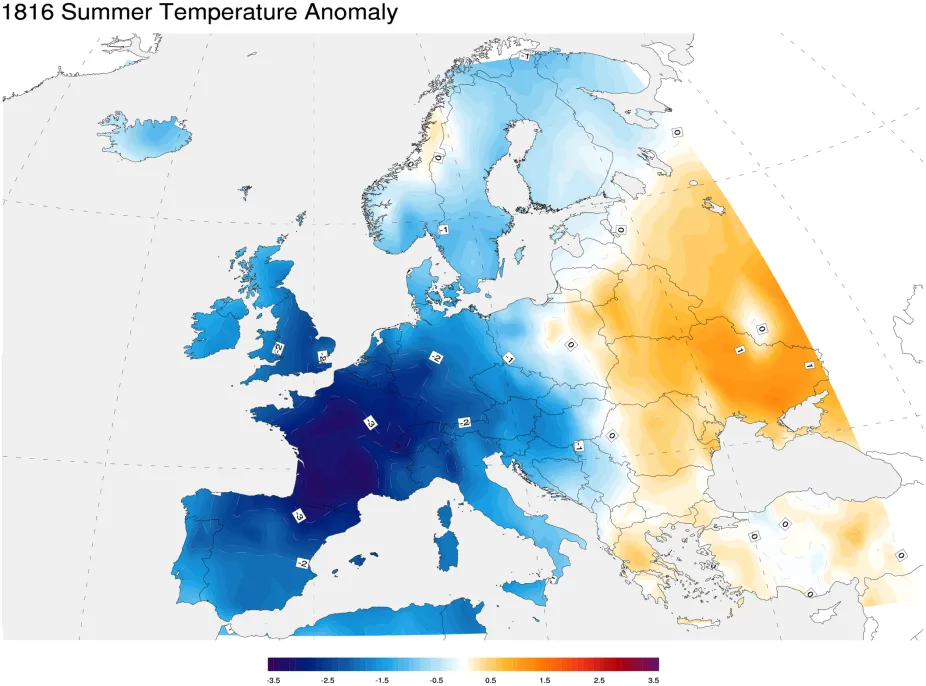

History warns us as well. The eruption of Mount Tambora in 1815 produced the “year without a summer” in 1816, dropping temperatures, as seen in the figure below, devastating agriculture across Europe and North America. Crops failed, famines spread, and tens of thousands perished.

More recently, Mount Pinatubo’s eruption in 1991 cooled the globe by about half a degree Celsius (0.9 degree Fahrenheit) for at least 20 months, disrupting rainfall patterns in the process. The eruption also depleted the ozone layer.

Scientists have also raised red flags about such schemes mimicking the Pinatubo eruption. A 2018 study in Nature Ecology & Evolution warned that solar geoengineering could “abruptly terminate” and trigger rapid global warming if deployment stopped. Researchers published a paper in 2022 in the journal Science of the Anthropocene, have cautioned that stratospheric aerosol injection could delay, but not prevent, ocean acidification, and could undermine incentives for emissions reductions. Back in 2014, LiveScience argued that “Geoengineering Ineffective Against Climate Change, Could Make Worse.”

These papers together strongly suggest that geoengineering via sun-blocking/aerosol injection is not a benign or risk-free option and that its consequences are highly uncertain, with many potential negative side-effects that are difficult or impossible to predict. Deliberately blocking the sun is not a climate solution—it is climate roulette.

Even advocates of the idea admit it is nothing more than a Band-Aid. As Hausfather and Keith acknowledge, “sunlight reflection is no panacea” and “treats the symptoms of climate change but not the underlying disease.” They also admit the risk of political dependency: once started, stopping a geoengineering program could trigger rapid warming rebound, a scenario far more destabilizing than gradual warming itself.

Steve Milloy, writing in the Daily Caller, explained why this notion is absurd. In “Trump’s EPA Is Right To Be Skeptical Of ‘Sun-Blocking’,” he highlighted that sulfur dioxide particles are air pollution—pollution that once drove acid rain and deadly smog events. Milloy sulfur notes that particles eventually fall back to Earth, meaning a program of perpetual injections would be required. “It sounds like a great business model on paper,” he wrote, “but people can’t just launch potentially dangerous air pollutants into the sky without some sort of guidelines and monitoring.”

The unintended consequences are not only physical but political. If wealthy nations take it upon themselves to inject particles into the stratosphere, what happens if poorer nations see droughts or floods as a result? International lawsuits and even conflicts could follow. The specter of “climate weaponization” looms large—as Milloy noted, the ability to control sunlight could be seen as a tool of geopolitical leverage.

The NYT itself might have cooled to the idea. Shortly after the op-ed was first published, the title was changed from “A Responsible way to Cool the Planet” to “Turns Out Air Pollution Was Good for Something.” Perhaps other scientists raised similar concerns as have been highlighted here and the NYT decided to walk back the “responsible” part.

The bottom line is this: blocking the sun to cool the planet is an inherently dangerous idea. Sunlight is the basis of life on Earth. Corrupting its distribution and intensity will not stabilize climate but destabilize societies. History, common sense, and scientific warnings all converge on the same conclusion: geoengineering by aerosol injection is not a solution but an invitation to chaos.

The New York Times’s op-ed promoting intentional sulfur pollution is a reversal of decades of clean air progress, representing climate recklessness, not climate realism.