The Associated Press (AP) claims in a post “Climate change is making coffee more expensive. Tariffs likely will too,” that climate change, in the form of severe weather like drought, is making coffee more expensive by suppressing yields. This is false. There is no evidence that severe weather is getting worse, In fact, coffee production is rising and the AP itself suggests some alternative reasons which are far more likely for any rise in coffee prices.

The AP reports that the destruction of some coffee plants “from heat and drought have cut production forecasts in Brazil and Vietnam, the world’s largest coffee growers.” They do admit that production globally is “still expected to increase, but not as much as commodity market investors had expected.”

Because of this, AP writes, coffee prices have risen.

This is a similar story to one Climate Realism covered back in February, “Sorry, New York Times, Climate Change Isn’t the Cause of High Coffee Prices,” but since the claims are persisting, it is worth revisiting.

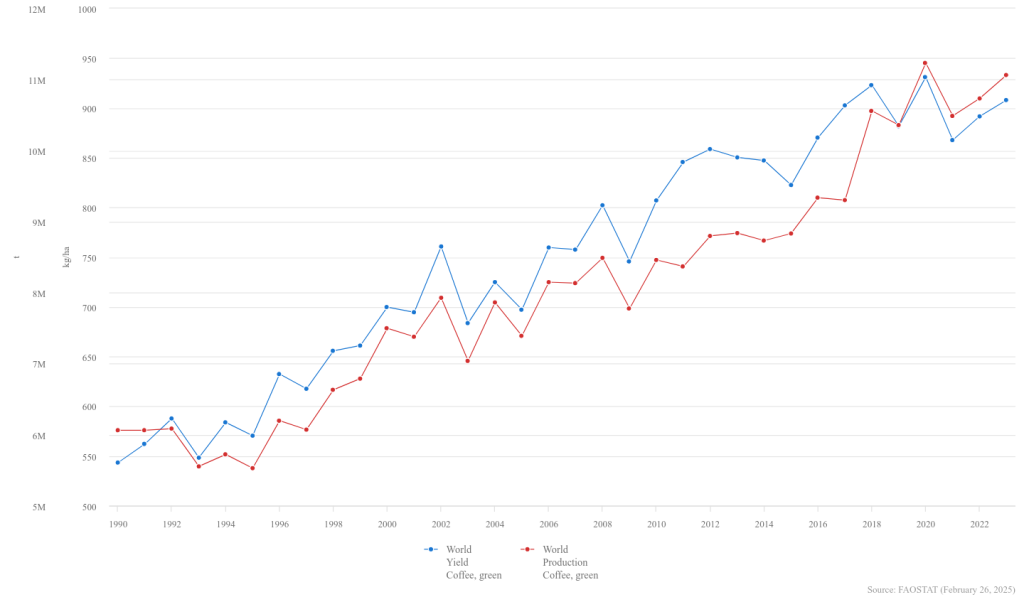

Looking at data from the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) – the AP is correct that world coffee production has climbed nearly continuously since the 1990s. As discussed in the other Climate Realism post, world coffee production has risen 82 percent, and world record production and yields occurred as recently as 2020. 2023 saw the second highest level of production ever. (See figure below)

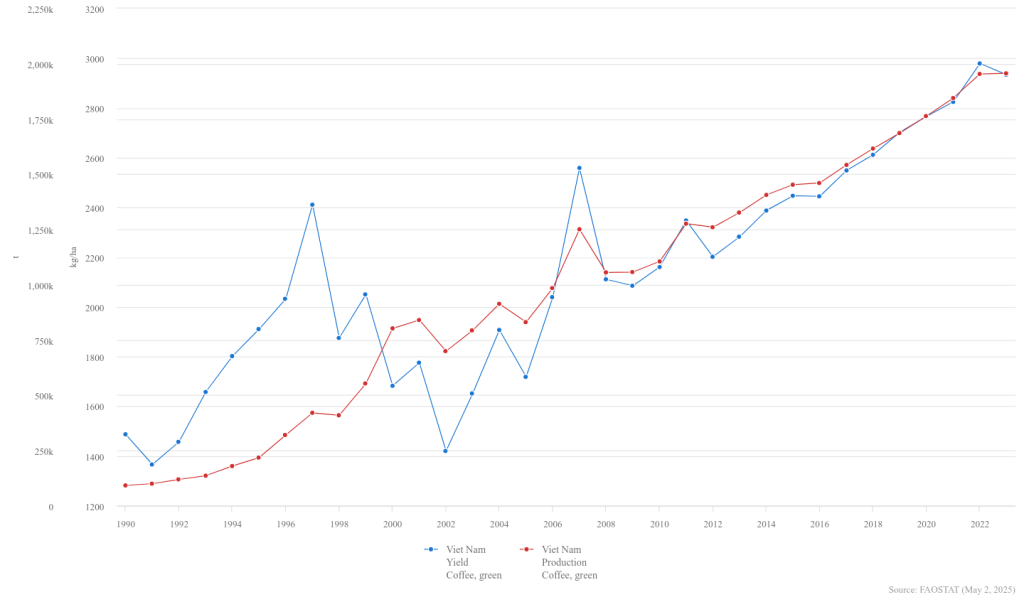

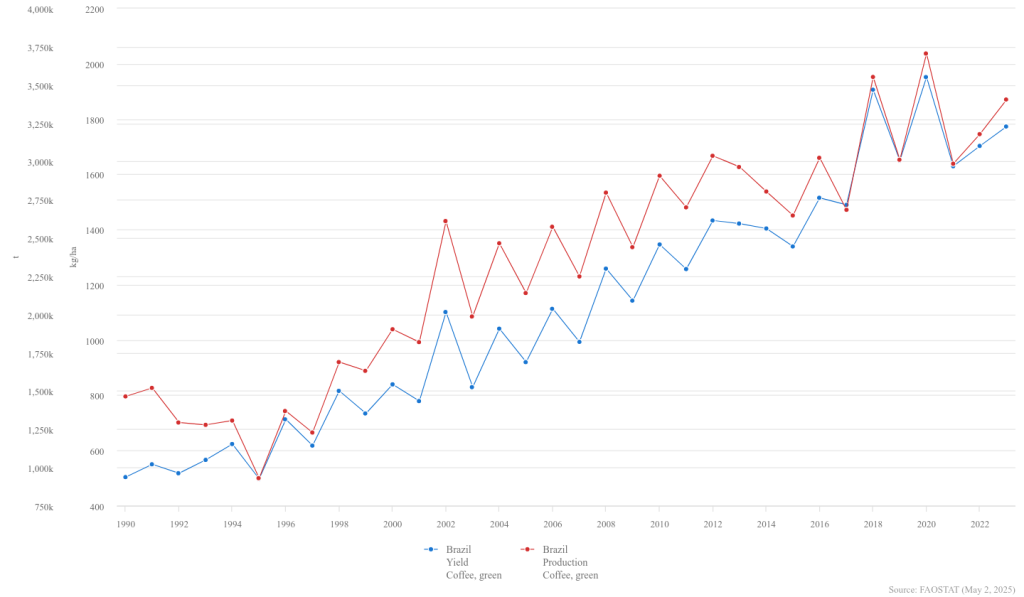

The specific countries that the AP claims have suffered recent losses, Brazil and Vietnam, have experienced trends of increasing production and yields over time, as well. In part, likely due to the fertilization effect of rising carbon dioxide emissions, that has occurred over the same time period.

In Vietnam, FAO data show coffee production has increased 2,026 percent between 1990 and 2023. (See figure below)

In Brazil, production increased 132 percent over the same period, with fluctuations between record breaking seasons from one year to the next. (See figure below)

It is difficult to find comprehensive, long-term drought and temperature data for Vietnam and Brazil. Brazil is often talked about in the news for some severe drought the country has suffered on and off for a few years now, particularly in the Amazon River Basin. Historical drought data, discussed in this Climate Realism post, does not show that recent drought is unprecedented or even connected to global warming. Worse droughts have occurred in the region’s past during times when global average temperature is believed to have been cooler than today. There does not seem to be a long term increase in the severity of drought Brazil. Deforestation is a likely culprit for recent dryness, as fewer trees in the Amazon make it harder for moisture to stay in the soil and maintain ground-level humidity.

A lower rate of increase in coffee production in a single year, lower but still an increase mind you, is neither evidence an impact of climate change nor portends doom for the future of coffee production. It is true that any given region has a maximum reasonable production capacity of coffee — but there is no evidence that peak has been reached yet anywhere, and climate change is not to blame either. Just as “peak oil” is an economic title and not an actual description of physically available resources, limits on coffee extend beyond the mere environmental. There are plenty of factors that limit crop production. Even the AP admits as much later in their article when says “[i]nflation is driving up the cost of labor, fertilizers, and borrowing.” The AP also explains that the expectation of tariffs may also push prices higher.

In February, the AP reported that the globe experienced a 14 percent decline in green coffee exports, which led to “the highest price ever for raw coffee in February, breaking the record set in 1977 when severe frost wiped out 70% of Brazil’s coffee plants.”

This doesn’t sound like the creeping pressures of climate change—since global coffee production is still much higher than during the 1970s, when emissions lower, temperatures were in the midst of a cooling trend, and scientists were warning of dangerous global cooling. It is clear that economic factors are the larger influences here.

The AP ought to have looked at a wider view of crop production data in Brazil and Vietnam, which may have assuaged some of their concerns about the future of coffee prices – at least as far as the influence of climate change is concerned. They do their readers a disservice, actually misleading more than informing them, by trying to tie every coffee price fluctuation to climate change, burying or downplaying the more direct economic factors.