A recent article in Bloomberg, titled “Mother Nature Is Coming for Your Cabernet,” makes the oft-repeated claim that climate change is threatening wine production, in this case, focusing on South Africa. This claim, as always, is false. In reality, wine production in South Africa in particular has done well over the past decades of modest warming, with no sign of any looming disaster.

The writer and senior executive editor at Bloomberg, Timothy L. O’Brien, described a conversation he had with a vintner in South Africa during a recent trip. He notes that winemaking is “just another version of farming” and that it’s “hard, unpredictable work.” This is true. All agricultural production is subject to sometimes unpredictable weather patterns over both short- and long-term time periods. Weather disasters are occurring all around the world at all times, so somewhere, some produce is being impacted. This is not new, and is not indicative of long-term effects from climate change.

O’Brien goes on to declare that climate change may make some of the most famous regions for wine production “inhospitable to grape production.” This statement is protected by the use of the word “may,” but in the context of the article, is clearly meant to be taken seriously. The possibility of major producing regions becoming “inhospitable” amid warming is extremely low, especially since data indicate that despite the last hundred-plus years of warming, grape growing and winemaking have not suffered.

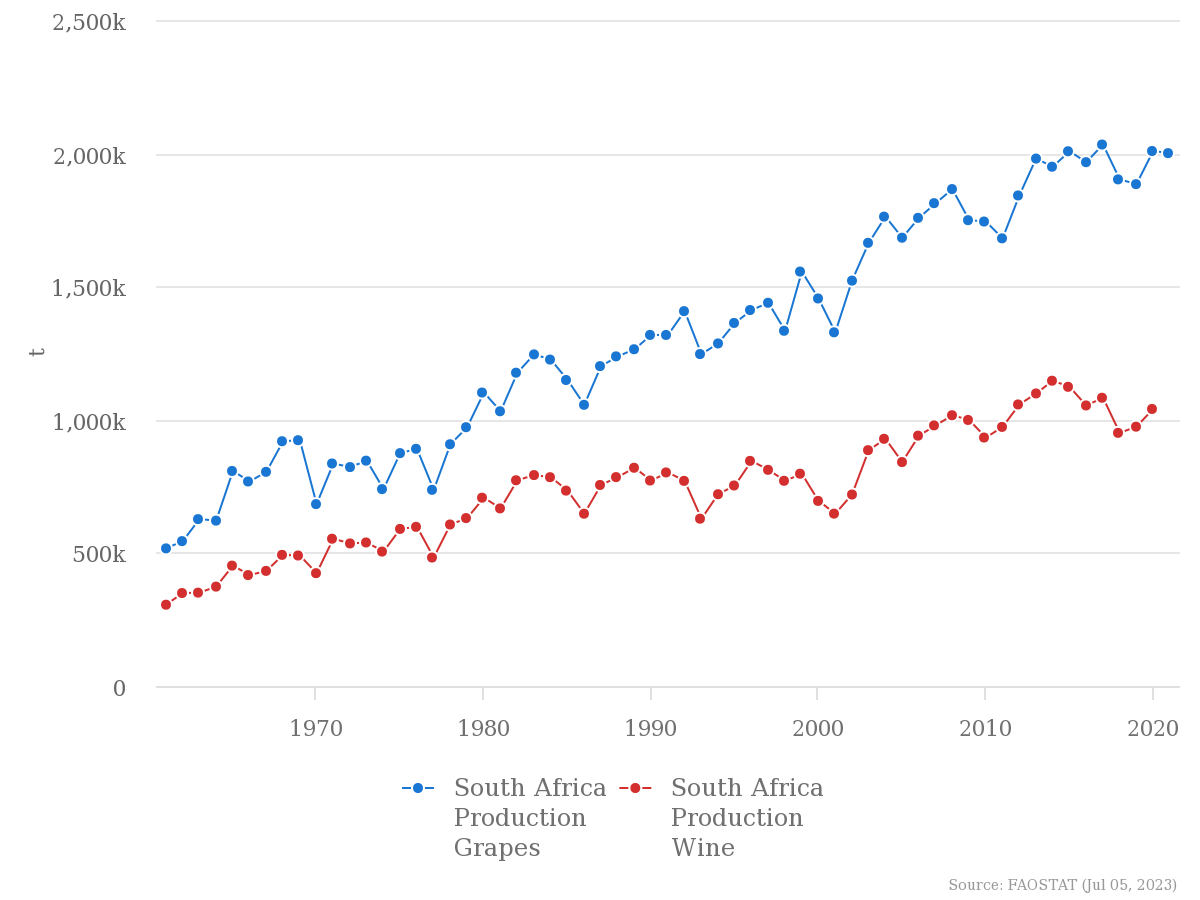

Indeed, the opposite is true, especially for South Africa. The available United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization (FA0) data on wine production in South Africa show that since FAO records began in 1961 both grape production and wine production have improved. The all-time record for wine production in South Africa occurred in 2014, and the all-time highest grape production was as recent as 2017. (See figure below)

FAO data shows that since 1961:

- Grape production in South Africa has increased 287 percent;

- Wine production has increased 240 percent.

Bad seasons will happen on occasion—they are all but guaranteed to for any agricultural business, but this is nothing new. As explained in almost a dozen previous Climate Realism posts on climate change and wine or grape production, winemakers and wine consumers are usually aware that some growing seasons produce better wines then others, hence the collecting of particular vintages from particular vineyards. It is the overall weather of the growing season that results in those differences from one vintage to the next, and for some wines it is more noticeable than others.

O’Brien made another puzzling comment, that grapes used for wine “require very specific conditions to grow,” and it’s certainly true that each grape variety prefers certain conditions, but the implication that wine all around the world is threatened because conditions may change is more alarmist than accurate. As O’Brien himself points out, major vineyards can be found all around the world in different climates and with different soil conditions, and the kinds of grapes that are selected for each growing region are based on what produces the best product for the region. There is no reason to suspect that vintners will stop selecting the most suitable grapes for their climate.

The owner of the South African vineyard O’Brien visited, Jean Engelbrecht, said that not only can weather patterns impact different regions in unpredictable ways, but nearby vineyards can see different weather as well. O’Brien explains that, while there was drought in South Africa that recently “sideswiped many of Jean’s local competitors,” in Jean’s area, “robust rainfalls plumped some of his recent harvests.”

This in itself indicates that local weather, not long-term climate change, is responsible any difficulties vintners face.

Bloomberg and O’Brien would do well to temper their impulse to attribute every weather-related seasonal, regional crop production decline to climate change, and instead look at the long-term data and trends to verify whether climate change might be playing a role. Concerns about wine and climate change are unsubstantiated by available data, history, and common agricultural knowledge.