Among the stories playing the blame game on climate change this week is one from Brittany Peterson and Matthew Brown of the Associated Press (AP) titled Changing snowfall makes it harder to fight fire with fire. Data shows the claim is completely baseless.

In the article, the writers claim that it is harder to set “control burns” i.e., fires intentionally set to safely burn off debris piles and vegetation which constitutes “excess fuel” that could fuel a catastrophic wildfire later.

“Western wildfires have become more volatile as climate change dries forests already thick with vegetation from years of intensive fire suppression. And the window for controlled burns is shrinking.”

Control burns are a worthwhile exercise in forest management, but the idea that these fires are now more difficult to set and manage due to “climate change” is false. First, let’s look at the issue of climate versus weather. The article makes this claim:

For parts of the Rockies, this winter brought too much snow, forcing officials to delay burns. Meanwhile, parts of Wyoming haven’t received enough snow to moisten the ground and allow fuel piles to be torched. Even when there is snow, that doesn’t mean it will last until the debris stops smoldering, said Brian Keating with the Forest Service’s Rocky Mountain region.

Regional differences of snowfall between states in a single season is weather, not climate. Climate is an average of weather over 30 years, according to official sources like the World Meteorological Organization (WMO). Note my highlights:

Snowfall amounts and locations varying from year to is entirely natural indication of a weather pattern, especially since the major drivers of weather (and resultant precipitation) in the Western United States are ocean patterns like El Niño and La Niña. These are opposite phases of a naturally occurring pattern in tropical Pacific Ocean that oscillate back and forth every 3-7 years on average. When in the warm phase, El Niño, much of the West gets more rain and snow, when in the cool phase, La Niña, the opposite occurs, and the west gets less rain and snow.

Therefore, a few years of wet or dry weather doesn’t equal a “climate change” effect. If a consistent trend were measured over 30 years, that would count as a climatic effect.

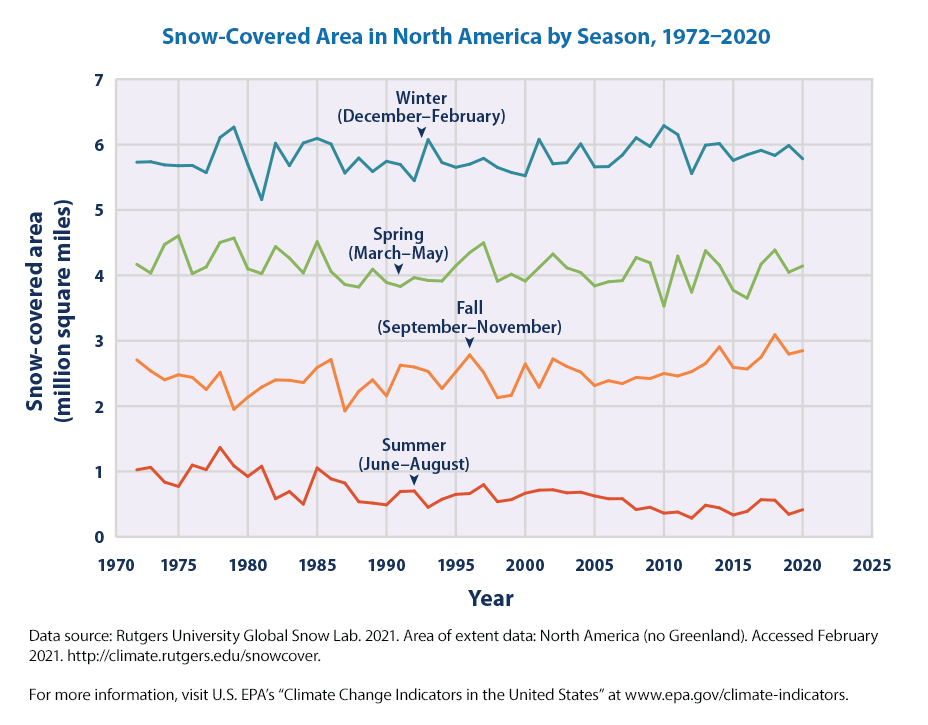

Then there’s the data itself. If you look at snow cover for each season in North America there’s not much indication of a lower trend, or higher variability in snow cover extent, as seen in Figure 1 below.

While there is a slight decrease in spring and summer snow cover, there is a slight increase in fall and winter snow cover, balancing out. Global warming aka “climate change,” if it were affecting snow cover wouldn’t be a regional effect like Colorado or Wyoming, or a seasonal effect just in the spring. At those scales, we are dealing with weather, not climate.

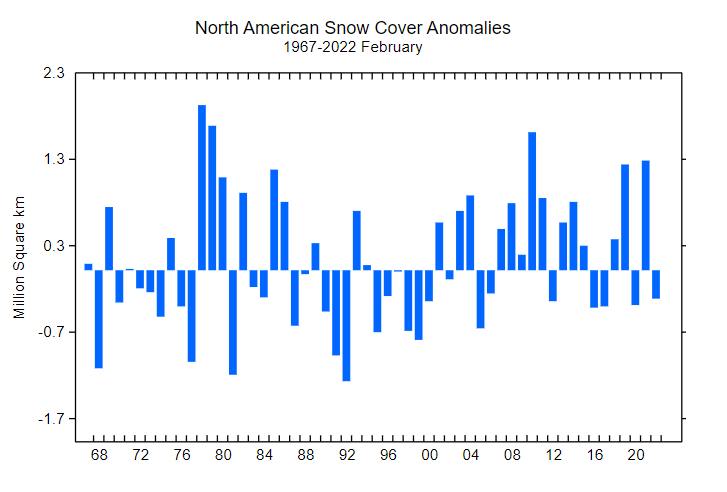

On the larger scale, there’s no evidence of any climate driven trend at all in the data, as shown in Figure 2.

Of particular interest is this quote from the article from Rutgers University researcher David Robinson, bold mine:

“One thing we know about climate change is it is increasing the variability and the extremes we are experiencing,” said Robinson. “Out West, once the season shifts, you get very dry, very quickly and it stays dry for months. So, you have a real tight window there.”

In Figure 2, the greatest variability of snow cover extent occurred from 1977 to 1981, during and after the inaptly named “Pacific Climate Shift,” which according to Columbia University, was driven by oscillations in the Pacific. Bold theirs.

“The 76/77 Climate shift. Between 1976 and 1977, the Tropical Pacific (the performing stage of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation phenomenon) underwent a rapid warming that had global impacts, including over North America, which was wetter than usual for the following two decades.”

That period was well before “climate change” ever became a buzzword, at a time when many scientists were warning of global cooling, and when carbon dioxide levels were significantly lower than they are today.

The bottom line is that while AP is quoting Rutgers snow lab researcher David Robinson, Rutgers own data disproves the claim of higher snow variability in the present leading to more difficulty setting and managing control burns.

It is sad that the AP, and Rutgers own employee, can’t even do a modicum of basic research before jumping on the climate change blame game.