A recent story on NPR’s Morning Edition, titled “Climate change and a population boom could dry up the Great Salt Lake in 5 years,” bemoaned recent historically low levels of the Great Salt Lake (GSL), tying the lake’s decline to two factors: climate change and population growth. The writer, Kirk Siegler, was only half-right. Population growth is arguably the prime factor leading to the GSL’s decline. The recent drought is likely another factor in this year’s low levels, however, because the current drought is not historically unusual, and is not part of a long-term trend of increasing drought frequency or intensity, climate change cannot be blamed for the GSL’s recent decline.

Maybe one small bright spot in an otherwise grim story of a looming ecological disaster. The lake doesn’t really stink anymore because it’s drying … and dying.

Scientists point to climate change and rapid population growth — Utah is one of the fastest growing states and also one of the driest — as the culprits. A recent scientific report from Brigham Young University warned that if no action is taken, the Great Salt Lake could go completely dry in five years.

Over two decades of the western megadrought, water diversions from rivers that feed the lake have increased in order to support farms and thirsty, growing cities.

Without action to reduce water diversions and withdrawals from the rivers and streams feeding the GSL, it may, in fact, disappear. Salt Lake City, the surrounding cities and mountain states in the region, are among the fastest growing in the nation. This has increased the demands for water from the rivers and streams feeding the GSL. However, contrary to Siegler’s claims, neither Utah, nor the region is in the midst of a long-term megadrought.

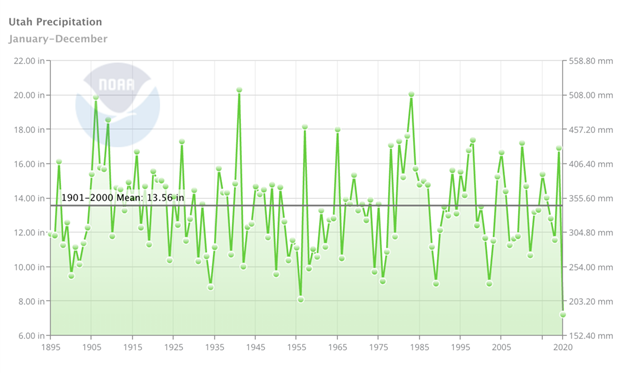

Utah is a relatively arid state, receiving just 13.56 inches of precipitation on average annually, much of it delivered in the form of snow. Utah has received below average rainfall for the past couple of years, although with recent winter storms, the drought has lessened modestly. However, data from the U.S. Drought Monitor show the state received well above average precipitation as recently as 2019, with 99.7 percent of Utah being drought free in July 2019, and only 0.3 percent listed as being abnormally dry. Utah also received well above average precipitation in 2016 and 2015.

Indeed, records from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration show that contrary to Utah being in a midst of a two-decade long megadrought; since 2000 Utah has experienced two years of approximately average rainfall, eight years of above average rainfall, and ten years of below average rainfall, meaning there is no evidence of a two decade long drought. In point of fact, Utah’s recent precipitation history resembles the state’s precipitation history since official record keeping began in 1895. (See the figure below)

As discussed in a prior Climate Realism, “No, Climate Change Isn’t Behind Great Salt Lake Decline,” because the GSL is a relatively shallow lake, modest declines in elevation or lake levels can amount to huge declines in area covered by water. During the present drought, the GSL did set a new record for low levels of 4190.2 feet in elevation in October 2021. However, that was only a foot lower than the prior record of 4,191.35 feet set in 1963. Tellingly, the previous record low elevation was set during a period when the earth was in the midst of a cooling trend and many scientists were warming of a pending ice age. It should also be noted that Utah’s precipitation in 1963, although slightly below average, was still more than 4 inches greater than Utah received in 2020.

Droughts come and go in Utah as they have throughout history and the data provides no support for the claim that climate change has made them more severe or frequent in the region. Indeed, as explained in Climate at a Glance: Drought, the current drought is a weather phenomenon of very recent vintage; not an indicator of long-term climate change. The U.N. IPCC reports with “high confidence” that precipitation has increased over mid-latitude land areas of the Northern Hemisphere (including the United States) during the past 70 years. Also, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration reports the United States recently underwent its longest period in recorded history with fewer than 40 percent of the country experiencing “very dry” conditions. The United States recorded its lowest percentage of land area experiencing drought in recorded history in 2017 and 2019.

Since the GSL has undoubtedly declined, and climate change isn’t a factor, what is? This is where NPR got the story right. Utah is one of the fastest growing states in the United States and it has been so for some time. When the previous low elevation record for the GSL was set in 1963, Salt Lake City had a population of approximately 387,000 people and was growing at an estimated rate of 3.2 percent annually. Today, although the city’s annual population growth has slowed, at 0.92 percent annually, it is still increasing faster than most other cities across the country. The most recent estimate of Salt Lake City’s population is 1,203,000. In other words, Salt Lake City’s population increased by approximately 211 percent, between the GSL’s previous record low and the most recent record being set.

The record is clear; rainfall patterns in Utah haven’t changed. Yes, the state is currently experiencing a severe drought, but it is a recent phenomenon, not part of a long-term trend. What has changed for the GSL, the primary cause of the present conditions there, is the huge increase in water users. There have been huge increases in demand for water for the millions of urban and agricultural users added to Salt Lake City and the surrounding area. The growing populace is drawing from the streams and rivers which historically have fed and replenished the GSL. Water volumes and flows have decreased in those rivers and streams not because weather patterns have, they haven’t, but rather because of increased users.

Will the GSL survive another five years or more? If rain and snowfall increases it should, for a while, but if population continues growing and ways of managing water use to keep or return more water to the rivers are not discovered and implemented, then the GSL’s days as “Great” may be numbered regardless of climate change.

I believe there’s a typo in “and many scientists were warming of a pending ice age.”

Should it not be “warning”?

As a Utah resident, I am now watching in horror as the State politicians try to stop the GSL’s decline. The last time they tried to change the lake’s depth was in the ’80s, when they spent millions to pump it out so it would not flood where there were new population centers. This was followed by several dryer years which nicely solved the problem for them; and they were left with egg on their faces.

No politician “remembers” this.

Now, “We have to stop this terrible calamity from happening!” spend, spend, spend…

Thank you, JimL

Politicians and the press in Utah were bemoaning the imminent demise of the GSL back when I was a Meteorology student there (1973-1975). As the graph shows, there has been little net change in precipitation since then; however, more of the water that does fall is being diverted into human activities.

So where is the water ‘diverted into human activities’ going? Is it evaporating from lawns, golf courses, swimming pools, etc.? Is treated wastewater going outside the basin?

Does snowmelt go to GSL?