A recent post at Bloomberg, titled “Climate Change Is Helping Pests and Diseases Destroy Our Food,” claims that recent crop shortages are due to increases in pest infestations and disease because of climate change. This is false for multiple reasons. First, the crops listed are not seeing substantial declines outside of particular production regions, which is to be expected from agriculture some years.

Bloomberg contributor Mumbi Gitau writes that pests and disease “are exacerbating crop shortages that have sent prices for goods like cocoa, olive oil, and orange juice soaring.” Gitau also asserts that these shortages will “become even more prevalent as extreme weather events multiply.”

To be clear data show that extreme weather events are not getting more frequent or extreme, even amid the last hundred-plus years of warming. Climate Realism has covered this fact many times, here, here, and here, for just a few examples.

While the article covers several foods allegedly threatened by climate change which have mostly been covered by Climate Realism before, including cocoa, olives, orange juice, grains, and tomatoes, the article places a bit more emphasis the first three, and so we will do likewise.

Beginning with cocoa, Gitau says “West Africa, home to two-thirds of global cocoa supply, has seen serious difficulties with its crop in recent seasons, causing wholesale prices to soar near historic highs this year.”

There are two main diseases attacking cocoa in West Africa, according to Gitau. The first is “black pod disease” – a fungal disease that is spread most easily in the wet conditions that parts of West Africa have seen. The other is swollen shoot virus, which is spread by pests that already live in warmer parts of the world, so there is no evidence modest warming is spread those pests to regions where they hadn’t previously existed.

Cocoa is typically grown in rainforests and warmer equatorial parts of the world, regions that are naturally susceptible to those diseases in the first place. Additionally, as explained in “Correct, CNN, Cocoa Prices Are Due to Natural Weather Conditions and Disease,” climate change is not necessary for these kinds of illnesses to break out in cocoa plantations. The International Cocoa Organization (ICCO) says on their website that “[a]verage yields for cocoa production are low due to extensive systems of cultivation, ageing tree populations, high incidence and poor control systems of pests and diseases, ageing farmer populations, shortage of affordable labour, lack of easily available inputs, poor extension services and above all, the use of poor/average quality planting material.”

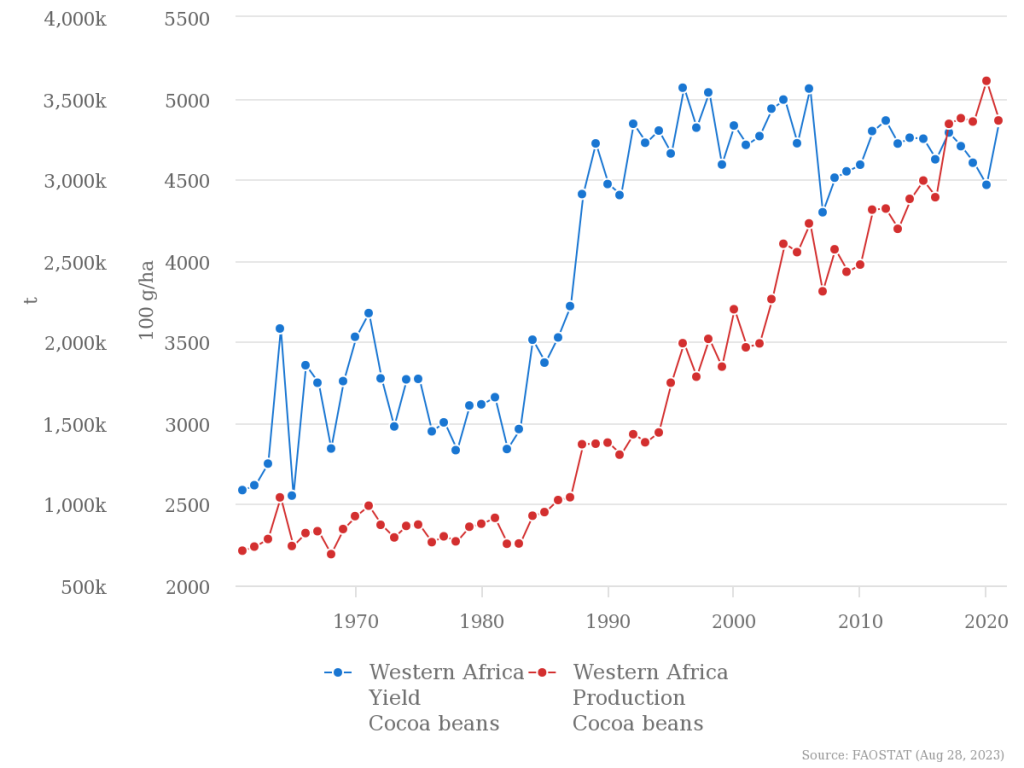

Because so much of the world’s cocoa is produced in a limited geographical area, any disease or poor conditions that strike the region will have a disproportionate impact on the total supply. Despite this, the same Climate Realism shows that world production of cocoa has steadily increased over time, despite fluctuations in yield. In fact, both yield and production of cocoa beans in West Africa have shown an increasing trend over period of modest warming, according to data from the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). (See Figure below)

- Cocoa bean production in West Africa alone has increased by 371 percent since 1961.

- Yield has increased 87 percent since 1961, though it has flattened off since the 1990s.

- Production records have been broken as recently as 2020, and have occurred 7 times from 2010 to 2021.

The article then says that olives, and olive oil, is threatened in Spain, “as drought has caused output to dwindle, more than doubling wholesale costs in the past year,” and by a plant-targeting bacterium that lives year around if winters aren’t cold enough to kill it off. Some famous, ancient trees in Italy are likewise threatened, but the report that Bloomberg links to as evidence blames “widespread agriculture abandonment” which allowed the insect that carries the disease to flourish and spread, whereas agricultural practices like tilling and cutting excess grass prevents the spread of the insect.

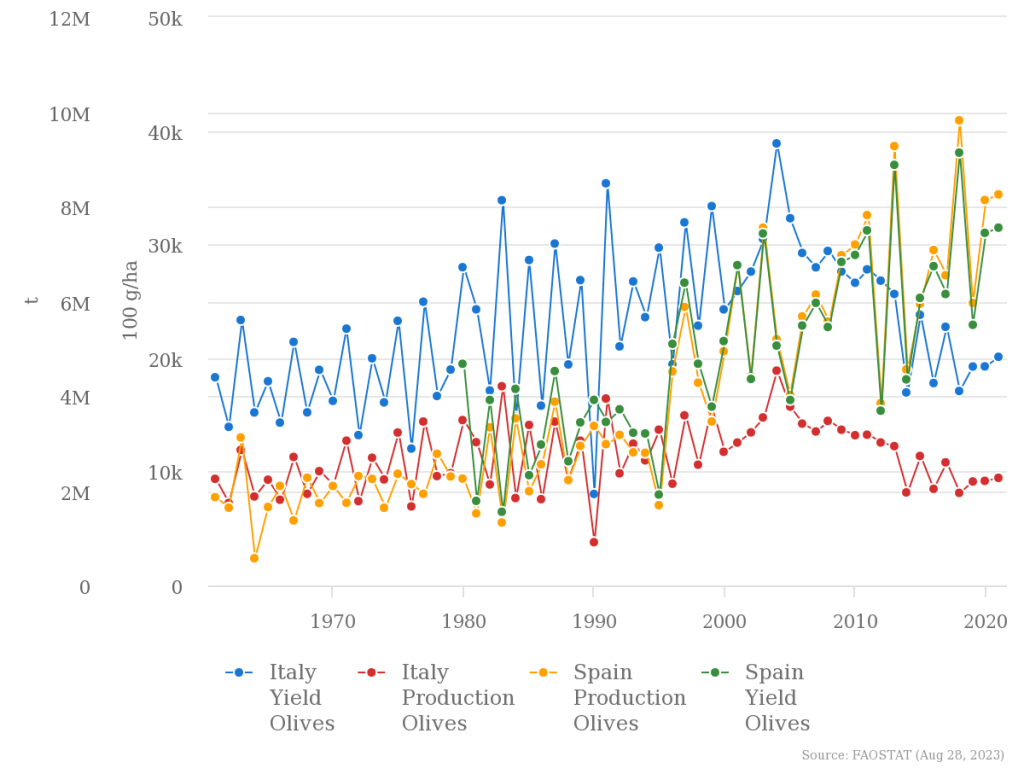

Although, according to U.N. FAO data, Italy’s production of olives has fallen off since it’s 2005 peak, Spain has meanwhile picked up the slack in a big way and is now the larger producer. (See figure below)

In Spain:

- Olive production has increased 343 percent since 1961;

- Yield has increased 61 percent;

- All-time production records have been set as recently as 2018, and records have been set four times since 2010 alone.

Finally, regarding orange juice, Bloomberg says “hurricanes, frost, and diseases have decimated orange groves in Florida, pushing US orange juice futures to record highs this month.” They also say citrus greening disease, spread by an insect, is likewise causing shortages. However, again, these problems are already endemic to warm weather zones where oranges are produced. Also, although bad weather like hurricanes can destroy fruit orchards and cause problems for years afterwards, data shows that the modest recent rise in global average over more than a hundred years has not caused an increase in the number or severity of hurricanes, as demonstrated in numerous Climate Realism posts. In addition, there is no evidence rising temperatures have negatively impacted orange production.

While this article points to the United States for proof of production woes, the United States has been growing fewer oranges for decades as the country is outcompeted by Brazil, China, and Mexico.

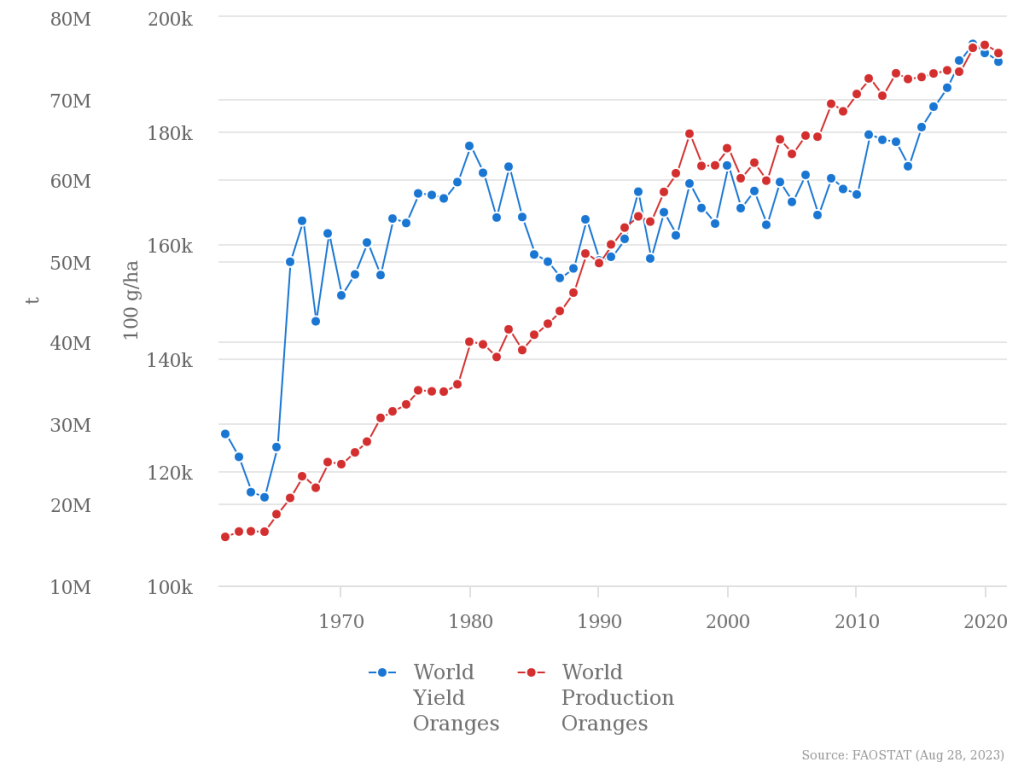

Looking again at available production data from the U.N. FAO, worldwide the production and yield of oranges has been rising for decades, with an amazing production increase of 372 percent since 1961. (See figure below)

Orange juice prices can be better explained by looking at historic price data. (See figure below)

Prices have been going up along with energy costs and supply chain issues, with a historic upwards trend starting around the time of the COVID pandemic lockdowns, certainly made worse by weather like hurricane Ian, but not exclusively driven by it. And one must consider the fact that energy prices have risen, in large part due to climate policies imposed by the Biden administration, in Europe, and in other industrialized nations, which have increased the price the pesticides and fertilizers made using oil and gas. Oil and gas restrictions have increased the price of producing, transporting, storing, and selling cocoa, olive oil, and oranges at retail outlets.

It may be tempting to believe that crop failures in different parts of the world are indicative of some major global climate change impact, however, long-term data in weather trends, pest and crop disease patterns, and production show no such trends. A more likely factor for the “appearance” of a crop apocalypse is the advent of the internet and instantaneous worldwide news, allowing us for the first time ever to now can see much more of what afflicts different crops around the world, coinciding with the media’s adoption of a climate crisis narrative in which every bad thing that happens can trace its cause to climate change. Regional crop failures have always occurred, causing difficulties for producers and consumers, but there is no evidence recent isolated crop declines are more than temporary or due to long-term climate change. Bloomberg, ostensibly a business and economics focused publication, should be aware of this, and be able to explain the intricacies without resorting to climate alarm.