A recent Forbes online article, “Here Are The Foods Hit Hardest By Climate Change In 2023,” claims that grapes and wine, blueberries, olives and olive oil, rice, and potatoes, are uniquely threatened by climate change, and suffered declines in production this year because of it. This is false. All crops have good and bad production years in different regions of the world, and data shows that each of these crops have increased dramatically as the planet has modestly warmed.

Senior contributor Daphne Ewing-Chow writes that recently, “global food security has been impacted by an increase in climate change related extreme weather.” She claims that extreme weather has lately been “characterized by hotter, prolonged, and more frequent heatwaves, and when coupled with associated consequences such as droughts, wildfires, and subsequent floods following rain, they have had severe impacts on food production.”

Ewing-Chow lists grapes and wine, blueberries, olives and olive oil, rice, and potatoes, as particularly threatened, each getting its own section. Ewing-Chow’s claims about extreme weather are false, as Climate Realism has shown repeatedly, so for brevity’s sake this post focuses on her false crop production assertions.

Forbes claims that grapes and therefore wine production are suffering from climate change.

Ewing-Chow writes that “[t]he International Organization of Vine and Wine (OIV) estimates that in 2023, global wine production was at its lowest in more than 30 years— with a reduction in grape yields of approximately 7% over 2022.”

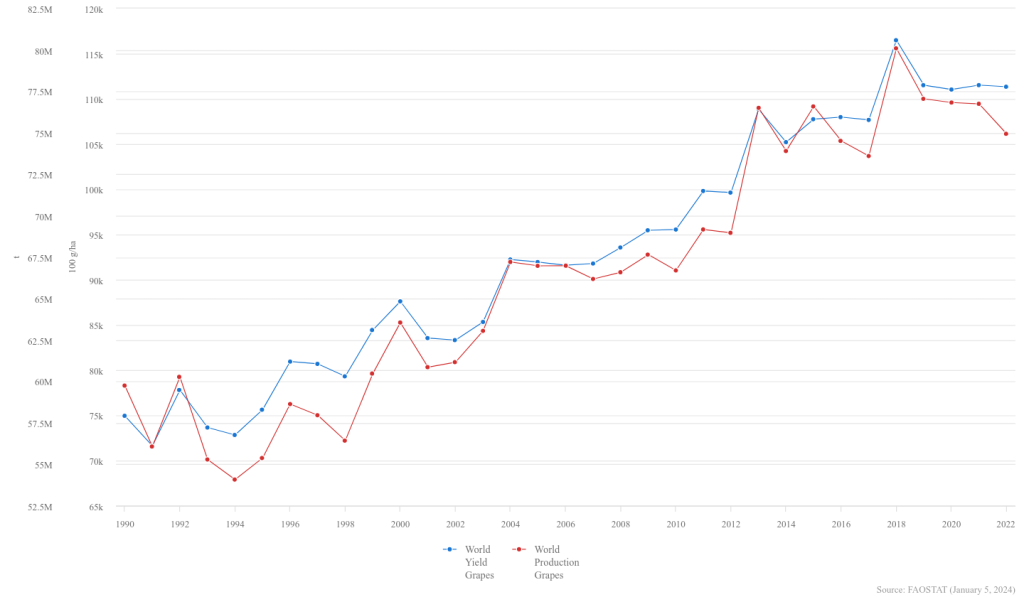

It’s important to note that wine production is complex and doesn’t always translate directly to how many grapes are grown, it also depends on markets and demand, which is clearly the driving force behind 2022’s low wine production, because while OIV reports that grape yields were down in 2022, the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization data show the long term trend is positive. (See Figure below)

From 1990 to 2022:

- Grape yields rose 48 percent;

- Grape production rose 25 percent;

- The highest value on record for yield and production was set as recently as 2018.

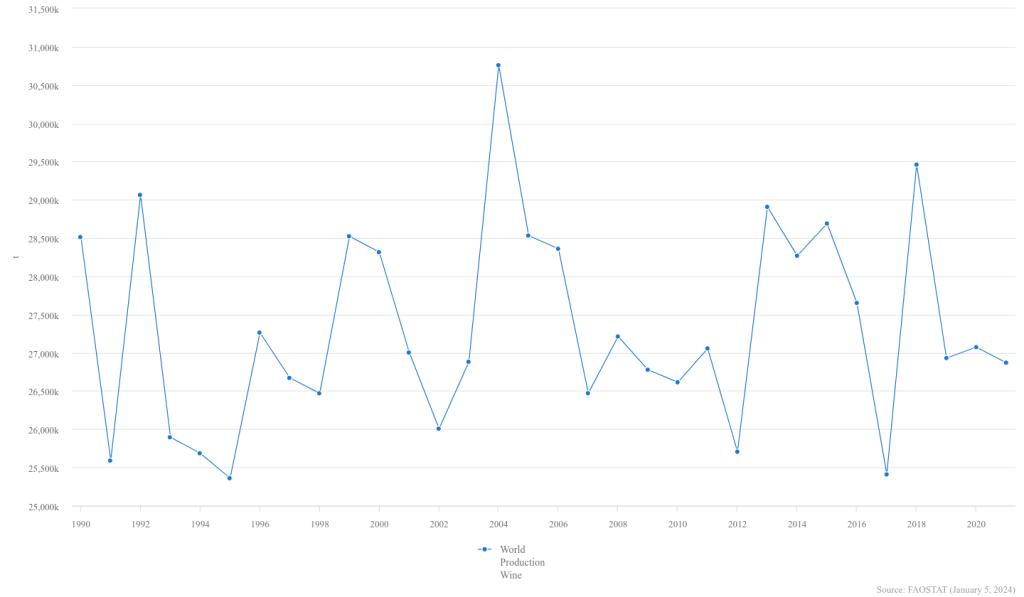

Wine production, on the other hand, varies wildly from one year to the next, with no clear trend. (See figure below) Data for 2022 and 2023 are not available from the FAO at the time of writing, but even if OIV is correct and the recent year was the lowest wine production year in the last 30+ years, it still doesn’t indicate a climate signal.

A narrow focus on production data, like comparing one year to the year prior, is not useful for indicating an impact climate change on agriculture, only long-term trends might suggest such impacts, yet there is no sustained trend of declining grape or wine production.

Forbes mentions Chile, Australia, and Spain as particularly effected, but strangely France is absent from the list. It’s notable France is left out of the discussion. The reason is that French winemakers saw such massive yields that they had to pay hundreds of millions of dollars to dispose of the excess, as discussed by Climate Realism, here.

The next food covered in the Forbes article is blueberries, which Climate Realism has covered previously when discussing American blueberry production, here, and here, for example.

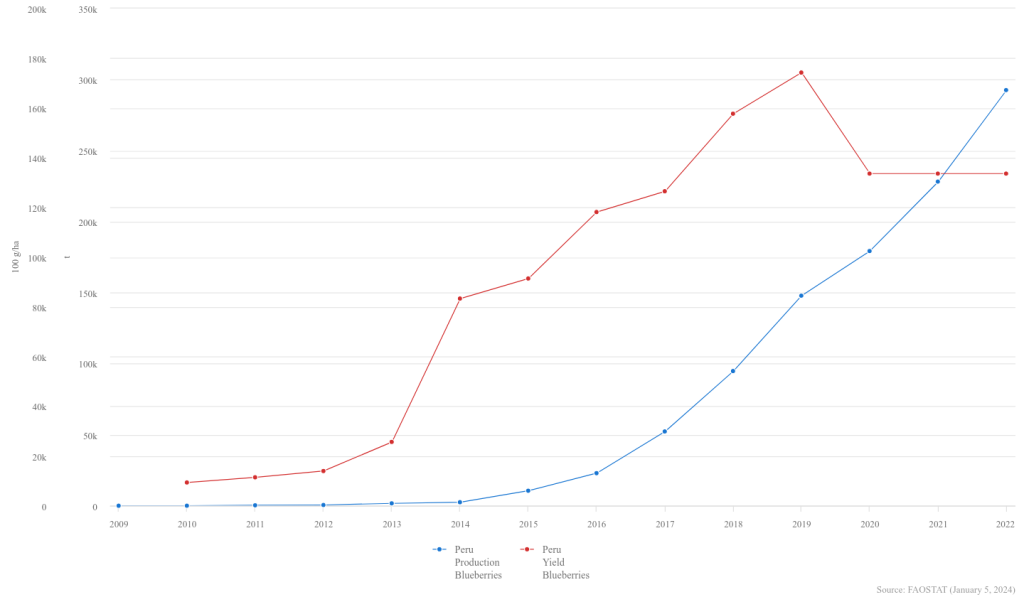

Ewing-Chow writes that the world’s top blueberry producing country, “Peru was significantly impacted by 2023 heat waves,” and “Peru’s blueberry exports declined by more than 50%.”

FAO data on Peruvian blueberry production and yields only goes back to 2010, but what it shows is a massive takeoff for the blueberry industry starting around 2015. (See figure below)

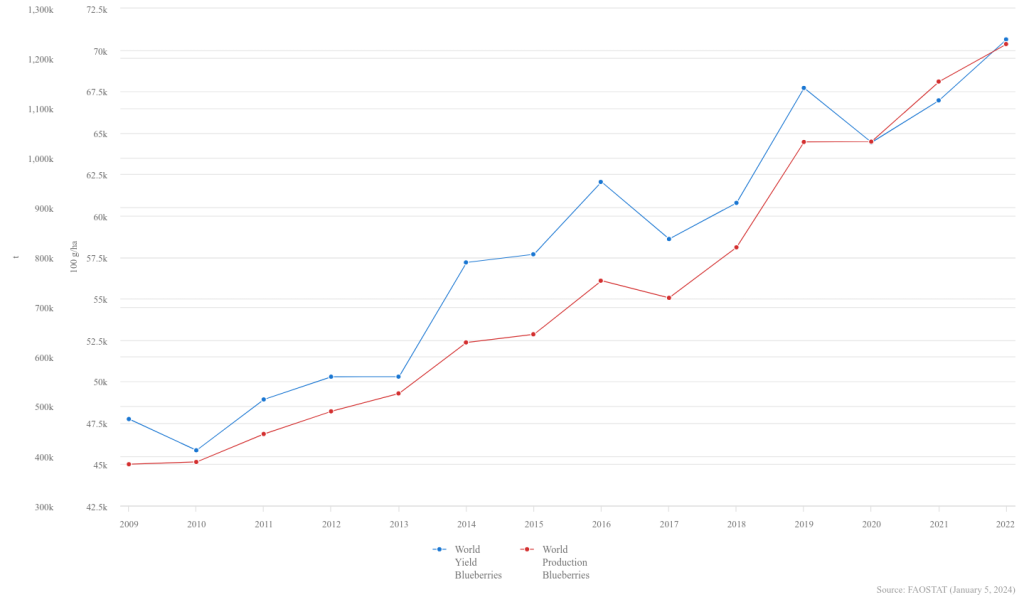

World data show a similar trend. (See figure below)

Since 1990:

- Yields rose 130 percent;

- Production rose an amazing 822 percent.

Next, olives and olive oil were likewise fingered as threatened by climate change, with Forbes reporting “low rainfall for over a year, leading to severe drought resulted in a 50% reduction in Spanish olive oil production.”

Climate Realism already has a few posts on this subject, including one from 2021 when similar claims were being made in the media. Back then, the International Olive Council reported that global olive oil production had more than doubled since the 1990s, and tripled since 1960.

More recently, in “Bloomberg Falsely Says Climate Change is Harming Crop Production, Reality Says Otherwise,” FAO data shows that Spanish olive production has increased 343 percent since 1961, and all-time production records have been set as recently as 2018, and records have been set four times since 2010 alone, during the decade that many mainstream media outlets have cited as the hottest on record.

Ewing-Chow also claims that rice production is threatened by climate change, writing “[g]lobal rice supplies tightened in 2023 due to climate impacts experienced across the United States, Asia and the European Union.”

However, once again, as documented numerous times by Climate Realism, rice continues to set records, the last world record set by rice production was in 2021. As explained using UN FAO data in “MSN Pushes Rice, Sugar, Tomato Crises – Despite New Crop Records,” every one of the five largest crop years occurred during the past five years, and “[a]ll 10 of the 10 largest crop years occurred during the past 10 years.” In other words, rice production continuously sets records amid climate change.

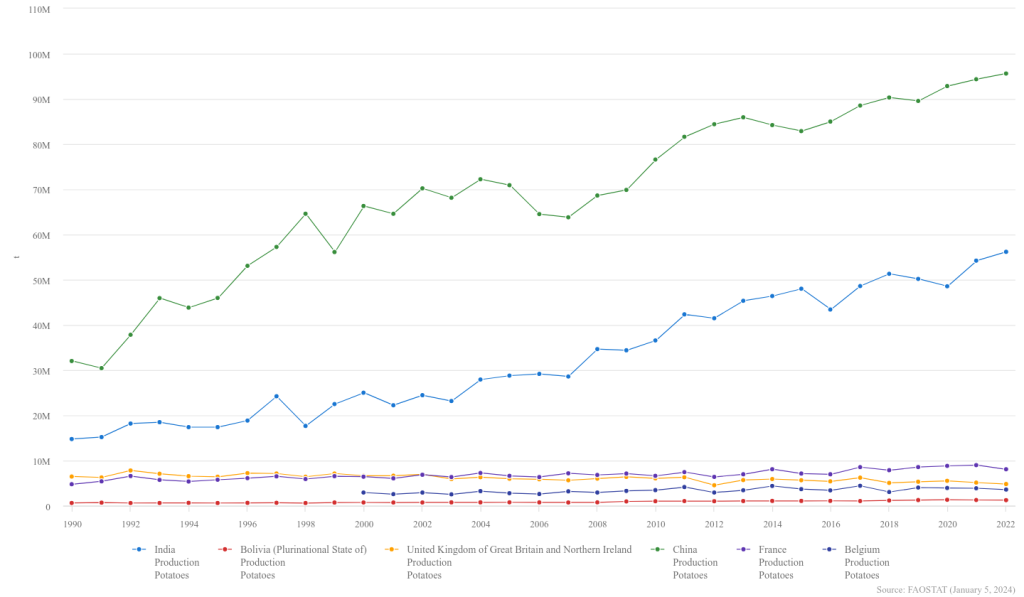

Last but not least Ewing-Chow discusses potatoes, citing a study published in the journal Climate, which “indicates that potatoes face a significant threat from climate change, with global yields potentially declining by 18% to 32% within the next 45 years in the absence of adaptation.” She points to recent poor yields in the UK, Belgium, and France, as well as Bolivia as proof that the study (all based on computer modelling) is likely correct. This is false reasoning. First, there is no reason to believe that adaptation will not be part of agriculture going forward, as it has been for all of history.

All of those countries may have seen recent lower production, however their contributions to the world’s potato production are utterly dwarfed by countries like China and India. (See figure below)

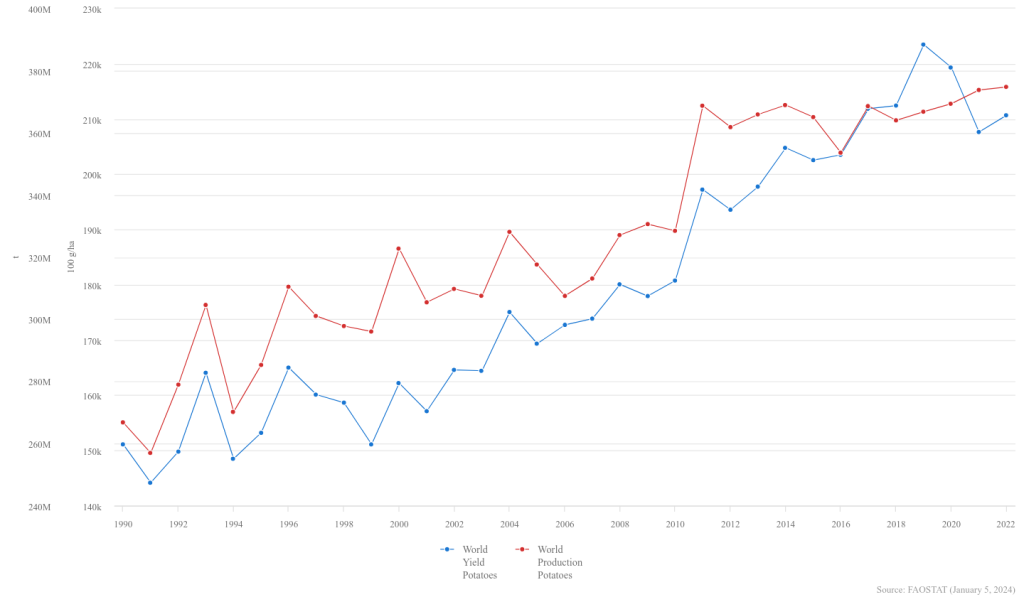

Worldwide, potato production is doing well. (See figure below)

Since 1990:

- Yields have risen 39 percent;

- Production has risen 40 percent;

- The most recent all-time record was set in 2022, second-highest in 2021, third highest in 2020.

Ewing-Chow is a senior contributor at Forbes, the website describes her coverage as “stories about food and agriculture through the lens of climate change.”

Maybe Ewing-Chow and her other climate-alarmed colleagues at Forbes, and elsewhere in the mainstream media, should remove the climate change goggles for a second and take a more holistic approach towards investigations into agriculture stories. To repeat, one year’s crop decline is neither proof of, nor necessarily a signal of, climate change, such cycles being normal throughout agriculture’s history. Only a declining trend would suggest climate change might be harming crops, but instead the trends for all the crops Ewing-Chow writes about are positive. Ewing-Chow is doing Forbes’ readers a disservice by inaccurately portraying food availability trends which are generally positive.

Another example of distorting the data to project doom and gloom for various crops! If this was the case we’d see massive price increases and lack of demand! Apparently demand is still there and people are not finding adequate supplies! This Forbes writer needs to take a course in statistical analysis 🧐 and variance and learn the difference between a one season change and a long term trend!

Another example of distorting the data to project doom and gloom for various crops due to climate extremes! If this was the case we’d see massive price increases and lack of demand! Apparently demand is still there and people are finding adequate supplies! Forbes reporter needs to understand statistics and variance and know the difference between a seasonal change in yield and a long term trend! Maybe actually spending time at one of these places would be good rather projecting a biased computer model estimate!