A recent article in The Guardian claims that economic damage from just a few degrees of global warming would be enormous. This is false, and the studies that The Guardian cites as making this claim are speculative at best, not peer-reviewed, and are likely falsified by the evidence.

The article, “Economic damage from climate change six times worse than thought – report,” presents an alarming perspective put forward by a pair of recent studies where economists predict that a 1°C increase in global average temperature results in a 12 percent decline in world gross domestic product (GDP). The Guardian writes:

Bilal said that purchasing power, which is how much people are able to buy with their money, would already be 37% higher than it is now without global heating seen over the past 50 years. This lost wealth will spiral if the climate crisis deepens, comparable to the sort of economic drain often seen during wartime.”

This is an unsupportable claim, considering the fact that the study focuses on a so-called “social cost of carbon” (SCC) which the economists calculated at $1,056 per ton, compared to the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) recently politically driven estimate of $190 per ton of emitted carbon dioxide—a figure that is much higher than previous EPA estimates and appeared, just like magic, when the Biden administration needed it to justify emission regulations on power plants and popular appliances. Other analyses, including previous EPA estimates, put the SCC even lower, or even positive under some conditions.

The SCC concept ignores the fact that there can be substantial benefits from increased atmospheric carbon dioxide, as well as costs. In a Climate Realism post “Social Cost of Carbon May Be Social Benefit of Carbon, Economist Finds,” an analysis put forward by economist and data scientist Kevin Dayaratna challenges the assumptions of the EPA’s calculations, pointing out that an accurate assessment would include at least the “positive agricultural feedback effects associated with carbon dioxide emissions.”

Dayaratna criticizes this metric because “social cost of carbon estimates are based on very questionable assumptions regarding the climate’s sensitivity to carbon dioxide emissions, naive projections reaching 300 years into the future, and ignorance of discount rate recommendations by the Office of Management and Budget regarding cost-benefit analysis.”

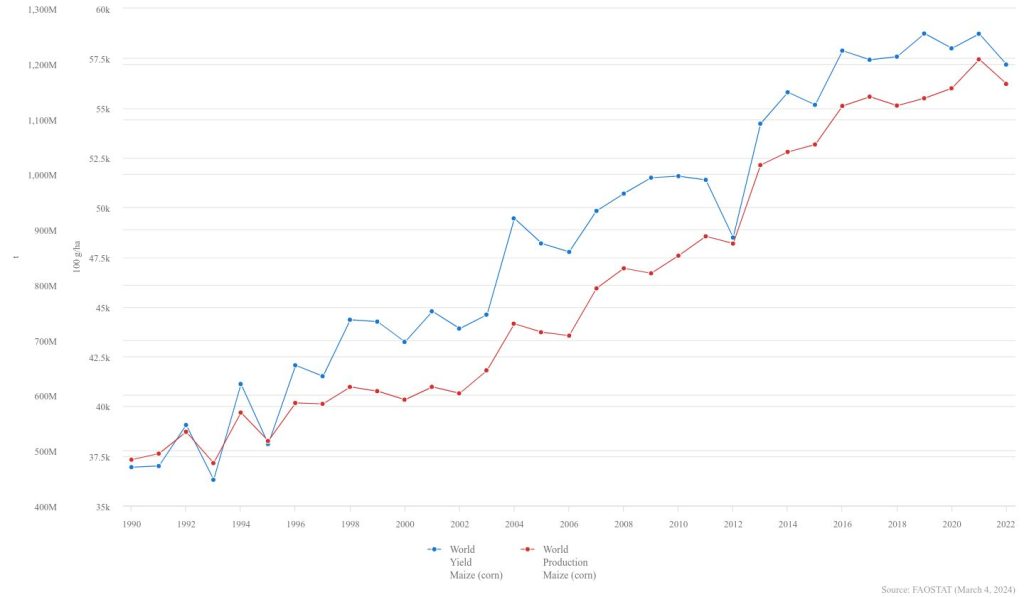

As shown in detail in dozens of Climate Realism posts covering region-specific and global agricultural output for various crops, agricultural output has increased dramatically over time amid modest warming. For a simple example, take a look at corn (maize) production globally over the past three decades. (See figure below)

Maize production has risen 140 percent, yield had increased 54 percent, since just 1990.

Additionally, contrary to the idea that global warming impoverishes the globe, poverty itself has been on the decline, as Climate Realism discusses here, and even climate-alarmist organizations like the World Bank say that extreme poverty may reach “global zero” by as early as 2030. In addition, perhaps the most powerful metric is lives lost to non-optimum temperatures. Research demonstrates that cold kills far more people around the globe than heat every year. As a result, the recent modest rise in temperatures has produced a decline in deaths and illnesses related to temperatures – which means more people actively participating in the economy. Why did the two economic studies promoted by The Guardian ignore this salient fact?

The studies referenced by The Guardian use unjustifiably low discount rates of 0.5 to 5 percent, despite the fact that the Office of Management and Budget recommend going up to 7 percent. A Heritage Foundation study found that in social cost of carbon analyses, re-running models using the 7 percent rate caused the social cost to drop by 80 percent in one model, and reverse to negative in another.

The studies also claim that “extreme” precipitation, extreme wind, extreme heat are all being caused by warming, and are going to get worse over time. In fact, from their statement that purchasing power should be 37 percent higher than it is now, it can be assumed that they assume these extreme weather events have already increased over the last 50 years’ of warming. This is false, refuted by available weather data. While average precipitation has increased over mid-latitudes, extreme precipitation has not. Likewise, flooding has not increased, there is no evidence that wind is becoming more intense, and measurements of extreme heat were higher in the past, with evidence suggesting that recent increases may be the result of urban development and the urban heat island effect biasing reported temperatures.

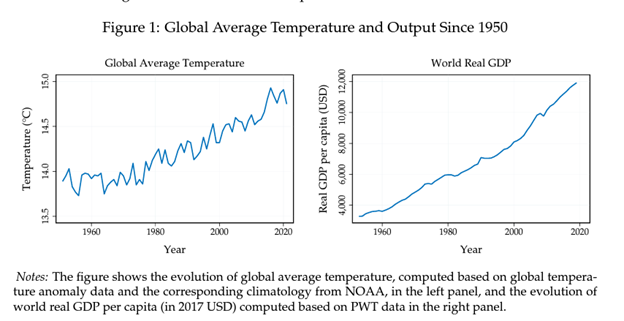

In their own study, the economists include side-by-side comparisons of global average temperature and world real GDP. Note that GDP grew steadily even as temperatures rose more erratically since the 1950s. (See figure below).

There is no evidence whatsoever, meaning real-world data, indicating GDP would have grown more if not for the recent modest warming, which should undermine their hypothesis that warming causes economic harm. Instead, the authors insist that while the “behavior of the two series in Figure 1 complicates the identification of the economic effects of temperature increases,” they chose not to focus on the “level of temperature as the treatment in our projections, but instead focus on so-called temperature shocks,” which they define as “potentially persistent deviations from the long-run trend in global mean temperature.” They admit that natural effects like solar cycles and volcanic eruptions can contribute to these shocks. The are acting like the wizard in the Wizard of Oz, who once Toto pulled back the curtain showing him to be nothing more than a man shouted, “ignore the man behind the curtain,” but in this case they are saying ignore the evidence to the contrary of economic growth amid (possibly partly because of warming) and embrace of our elegant hypothesis predicting economic decline from climate change.

The researchers do temper their claims by saying that economic gains will still occur, just not as much as would have otherwise, but this is impossible to confirm, and is based upon model backcasting. Yet models have been consistently unable to accurately reflect past and present temperatures, much less weather impacts, without constant “adjustments.” No one can know what economic growth would have been. But we know computer models designed to forecast temperatures don’t get them right, so why should anyone trust, or a prominent news organization tout, the economic projections of models informed by flawed climate models. It’s a case of Garbage In, Garbage Out, GIGO. Computer models forecasting the future (or trying to model the past) are not real life, but rather model projections whose outputs are only useful to the extent they they mirror actual conditions — which these don’t.

Worst of all, The Guadian concludes with the declaration that both papers “make clear that the cost of transitioning away from fossil fuels and curbing the impacts of climate change, while not trivial, pale in comparison to the cost of climate change itself,” which given the above information, they certainly do not. Shutting down fossil fuel production and use would be catastrophic in ways the economists in these studies ignore or fail to consider, such as the impact on agricultural yield and the cost of consumer goods, tax revenue, not to mention electricity production. Banning fossil fuels would stagnate third world development, and plunge many more into poverty.

The Guardian, by now infamous for promulgating falsehoods about climate change and energy policy, is probably not at all ashamed of pushing yet another false climate change scare story, but it should be.

The Guardian is probably one of the world’s most dishonest newspapers.