The World Meteorological Organization’s (WMO) article, “Climate Change Impacts Grip Globe in 2024,” paints a dire picture of a planet spiraling into chaos, with extreme weather events attributed to anthropogenic climate change. While the narrative is emotionally compelling for low-information readers, it falsely conflates short-term weather events with long-term climate trends. It is a fundamental error that undermines the scientific integrity of the claims, especially since the WMO itself actually defines what climate is: “…the average weather conditions for a particular location and over a long period of time.” Furthermore, historical data reveals that humanity is not facing an escalating climate crisis but has instead become more resilient to extreme weather, with weather-related deaths plummeting over the past century.

One of the core flaws in the WMO article is its failure to differentiate between weather and climate. Weather encompasses short-term atmospheric phenomena, such as heat waves, storms, and rainfall, while climate refers to long-term patterns and averages over decades or centuries. The distinction is crucial, yet the WMO blurs the line by implying that individual weather events in 2024 are definitive evidence of climate change. Only long-term trends of thirty years or more in weather can indicate climate change, and no such long-term trends in worsening extreme weather events are found in the data.

As highlighted by Climate Realism, “Extreme weather events have occurred for millennia, often with no connection to human influence.” The site notes that attributing every flood or heatwave to climate change ignores natural variability and fails to account for the complexities of atmospheric systems. Even the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) acknowledges the difficulty of attributing specific weather events to long-term climatic trends, stating that such attribution requires rigorous analysis and cannot rely on anecdotal observations.

In short, the WMO’s approach is highly misleading, using weather events as propaganda tools to sell the narrative of a climate emergency.

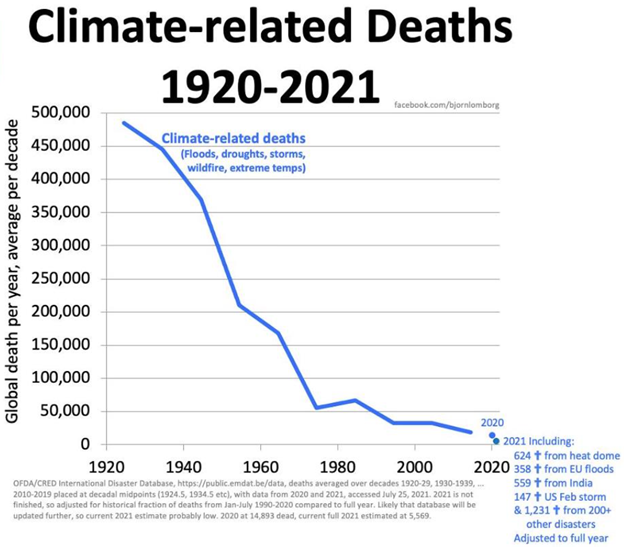

While the WMO’s article focuses on the immediate impacts of extreme weather, it conveniently omits a critical fact: deaths from weather-related disasters have plummeted over the past 100 years. In the 1920s, the global average annual death toll from such disasters was approximately 485,000. Today, that number has fallen by over 98%, to fewer than 10,000 annually. This is not evidence of escalating danger but of extraordinary human progress. See the figure below.

As detailed on Climate at a Glance, the dramatic decline in weather-related fatalities is due to advancements in forecasting, emergency response, infrastructure, and communication technologies. Humanity’s ability to anticipate and adapt to extreme weather has improved exponentially, saving millions of lives and mitigating the impacts of natural disasters. Far from being more vulnerable, we are more resilient than ever before.

Additionally, Watts Up With That highlights that while global news reporting on extreme weather events has increased—creating the illusion of worsening conditions—the actual frequency and intensity of such events remain within historical norms. This underscores the importance of context, reminding readers that cherry-picking extreme events while ignoring overall trends leads to badly skewed public perceptions and expensive government policy missteps.

Another flaw in the WMO’s argument is the assumption that all unusual weather patterns are the result of human activity. While the climate system can be influenced by some anthropogenic factors, it is also highly subject to natural variability. Phenomena such as El Niño, volcanic activity, and solar cycles play much larger roles in shaping weather patterns and must be considered when assessing the causes of extreme events.

For instance, the WMO’s article references record-breaking rainfall and floods in 2024, implying these are unprecedented. However, as noted by Climate Realism, historical data shows similar events occurring long before industrialization. Ignoring this historical context creates a distorted view of current conditions and fosters unnecessary alarmism.

The WMO’s approach is emblematic of a broader trend in climate reporting: using short-term weather events as proof of long-term climate change. This tactic is not only scientifically flawed but also dangerously misleading. By conflating weather and climate, such narratives erode public trust in science and promote policies that are often more harmful than the phenomena they aim to address.

Such alarmist rhetoric has real-world consequences, driving economically disastrous policies that disproportionately harm the world’s poorest populations. For example, diverting resources toward combating exaggerated climate threats can leave communities less prepared for immediate challenges, such as poverty, disease, and actual natural disasters.

The WMO’s “Climate Change Impacts Grip Globe in 2024” exemplifies the misuse of short-term weather events to promote a long-term climate crisis narrative. Such sensationalism not only undermines public understanding of climate science but also fosters misguided policies that prioritize fear over fact. Weather is not climate, and conflating the two is either an act of ignorance or deliberate deception, either of which can lead to misdirected resources, endangering peoples’ lives and well-being.

The public should hold climate reporting to a higher standard—one that prioritizes scientific accuracy over sensationalist headlines. The stakes are too high for anything less.