A recent article in the Wall Street Journal (WSJ) describes 2022’s wildfire season as relatively quiet, attributing a decrease in fires to an increase in rainfall, cooler temperatures, and the efforts of firefighting organizations.

The article, “Wildfire Season in U.S. West Ends With Fewer Blazes, Less Damage,” explains that this year has had fewer serious fires than years past.

Jim Carlton, writer at WSJ, writes:

One of the slowest wildfire seasons in years has come to an end in the West thanks to well-timed rain and cooler temperatures, bringing a reprieve to a region hit by numerous destructive blazes over the past several years.

The break is giving firefighters an opportunity to focus on prevention efforts such as thinning forests that could lessen damage from wildfires in the future, according to officials.

While rain and cool weather are certainly contributors to keeping fires down, an element that cannot be understated or ignored is the presence of easily-combustible material. The WSJ piece notes the critical role that tree thinning, if allowed, can play in preventing fires and reducing their severity when they occur.

“[T]he Washburn Fire in July threatened the Mariposa Grove of Giant Sequoias in Yosemite National Park, but the trees escaped harm after the blaze slowed to a crawl when it hit areas previously thinned by park crews,” wrote Carlton.

A prior Climate Realism described the problematic situation that arose when the environmental activist group, the Earth Island Institute, sued Yosemite National Park to prevent planned tree thinning in the park. They claimed that dead tree density was “irrelevant” to wildfire prevention. Professional foresters, park managers, and almost any other rational person knows this is wrong.

Wildfire requires an ignition source, oxygen, and fuel. Dry invasive grasses, as discussed in one Climate Realism article, often fuels fires. Dead and dying dead trees and dry underbrush are an even more common source allowing fires spread farther and burn more intensely.

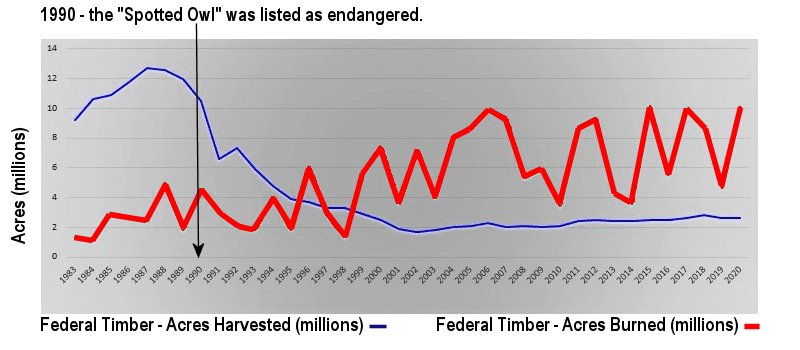

The logging industry once maintained forests across the West; building roads that were used by firefighters to access hard-to-reach parts of the forests before seasonal wildfires could spread to populated areas, thinning out dead and dying trees, and keeping the underbrush under control. After the spotted owl was listed as endangered, however, logging all but totally ended on many federal lands in the western United States, and severely restricted on others. Wildfire trends suggest a strong correlation between the decline in active forest management, in large part through logging, and the closure of thousands of miles of forest roads, and the recent increase in Western wildfires. (see the figure below).

The WSJ article reasonably downplays any connection between climate change, this year’s relatively slow wildfire season, or previous seasons’ bigger wildfire seasons, because there is no evidence linking rising carbon dioxide levels and wildfire activity. Recent years have been far from the most active for wildfires. Historical data show that in the early 20th century, a hundred years of global warming ago, forest fires were much more extensive than in recent years.

Wildfires are common enough to have a season named after them. All it takes is the right combination of conditions. This year, as the WSJ accurately reported, the conditions were not favorable. The hope portrayed in the WSJ story is that this year’s slow season allowed forest managers time to reduce fuel loads significantly in order to prevent large wildfires in the future, even when weather conditions turn favorable once again for extensive wildfires.