The Associated Press (AP) claims in a recent article, “Earth’s lands are drying out. Nations are trying to address it in talks this week,” that a substantial percentage of the land on earth is drying out due to human-cased climate change. This is false. Not only does data contradict this claim, but the AP leaves out details from the report which make the relationship between aridity and the modest warming of the past century much less certain.

The study, or report, rather, that the AP based their article on is the recent United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) report. It should not surprise anyone that the UNCCD is hyping alleged desertification, and indeed the AP makes it known that the UN’s interest is not in reporting on conditions around the world, but in securing tens of billions of dollars to “address” the effects of drought in 80 countries.

The AP writes that “[m]uch of Earth’s lands are drying out and damaging the ability of plant and animal life to survive, according to a United Nations report released Monday at talks where countries are working to address the problem.” They continue, “once-fertile lands turning into deserts because of hotter temperatures from human-caused climate change, lack of water and deforestation.” Among the risks identified by AP are food insecurity due to low yields and livestock, and migration that is often wrongly called a climate refugee crisis. Climate Realism has previously discussed why those alleged risks are not what they appear, in that food production is skyrocketing even in regions that are supposedly suffering this supposed desertification, and there actually have not been climate refugees but rather economic, political unrest, and weather-disaster related migration.

The AP only briefly mentions that the UNCCD itself, while alleging that human-caused climate change is the “primary driver” of the so-called “aridity crisis,” also acknowledges that land use changed impact local drought conditions. This is being downplayed significantly, as it is known that deforestation has a significant local impact on humidity and rainfall. This was the real culprit behind many headline-making local droughts in South America, which Climate Realism covered here, here, and here.

A large portion of the report also involves the writers justifying their use of the “aridity index” (AI) which represents the ratio of precipitation to potential evapotranspiration over time. The UNCCD report admits using that metric “as a reliable indicator of current and future trends in aridity is controversial.” The report is also, predictably, heavily reliant on model reconstructions of past conditions.

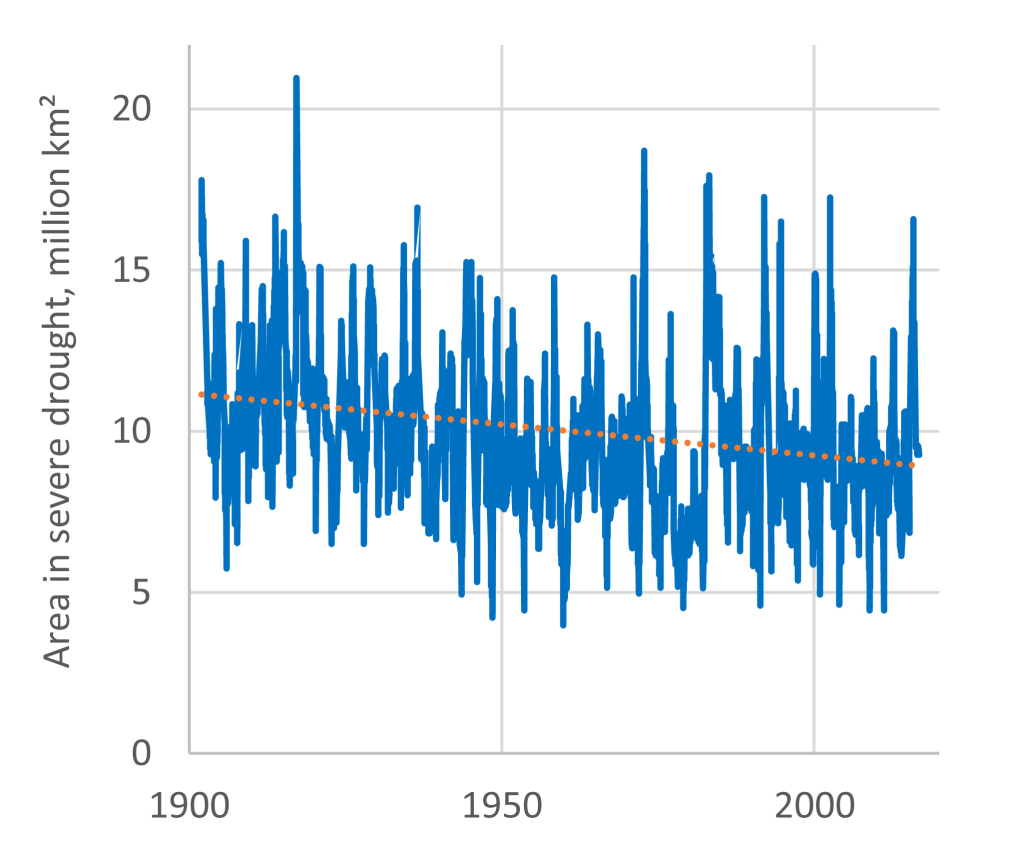

Beyond those issues with the AP’s claims there is another: available measured drought data does not show that drought is getting worse or more common. For instance, in a recent paper published by Bjorn Lomborg in the journal Technological Forecasting and Social Change, Lomborg points out that the World Meteorological Organization recommends that the Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) be used to analyze meteorological (precipitation related) drought. That drought monitoring tool is widely used, and calculated how much a region’s precipitation is deviating over a particular time period. When applied globally, it shows no increase in meteorological drought. (See figure below)

Available data also show that precipitation has increased at least over northern mid-latitudes over time.

But that is just precipitation-related, or meteorological drought, what about hydrological drought, or agricultural drought?

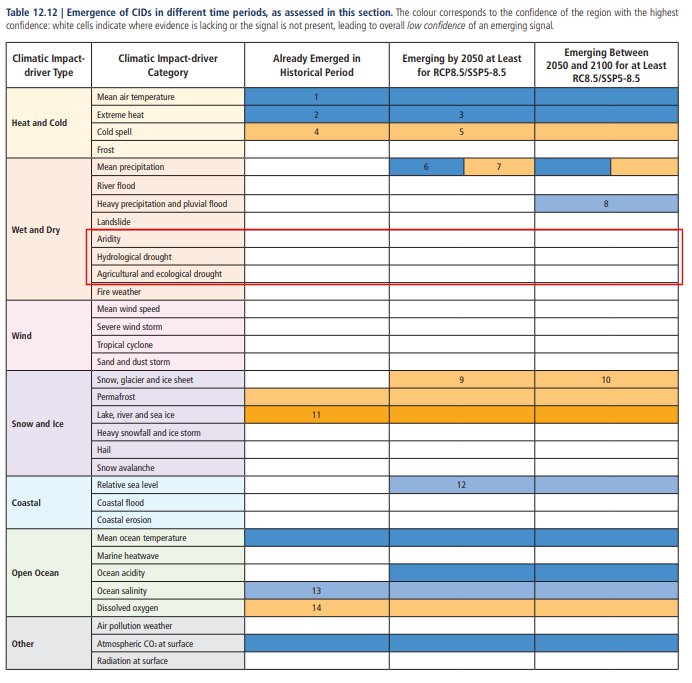

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s AR6 report chapter 12, available data does not indicate that those types of drought are emerging as “climate indicators,” nor does it indicate increased aridity as a consequence of climate change has emerged or expected by years 2050 through 2100. (See figure below with those items boxed in red)

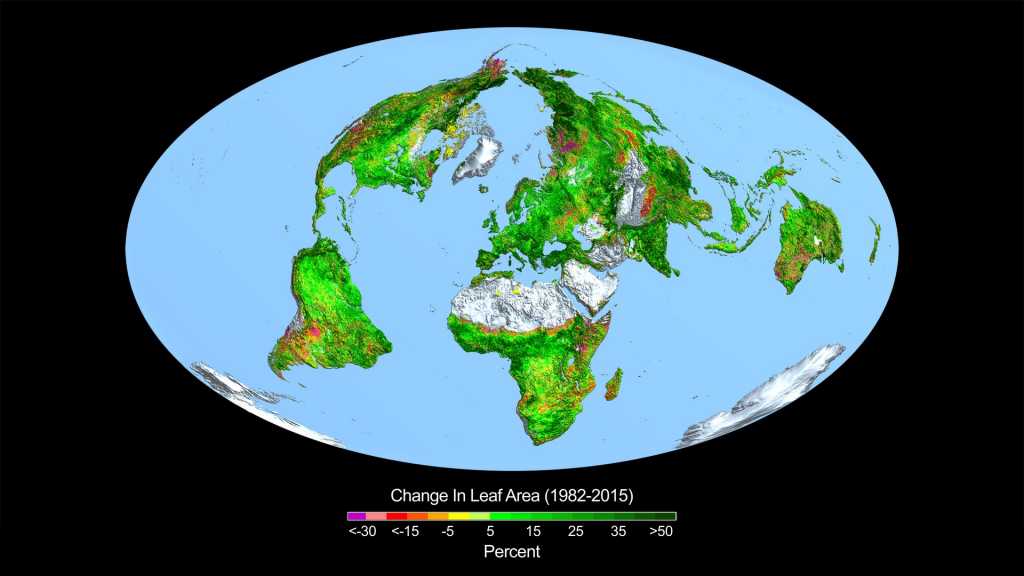

Another metric to look at global drought conditions and desertification are trends associated with vegetation. In Climate at a Glance: Global Greening, it is very clear that the most significant portions of the planet that can see vegetation growth are seeing it, rather than reductions in vegetation that increased aridity would indicate. NASA satellite data show that areas seeing declines in leaf coverage are far more limited than those seeing massive increases. (See figure below)

The NASA data seems to back up earlier research that found the increase in atmospheric CO2 between 1982 and 2010 actually resulted in up to a 10 percent increase in vegetation coverage in even warm, arid environments. This is measured data, not computer models with presumptions about global warming and evapotranspiration coded in.

The AP is simply uncritically parroting the UN’s claims that the planet is “drying out” without bothering to check the plethora of easily available data that would call the UNCCD report into question. The most charitable case that can be made for the AP is that they don’t understand the difference between observed versus modelled climate conditions, but it is far more likely that they simply do not care. The AP would rather push climate catastrophism than fairly analyze reality.