A story published by CNBC claims climate change is damaging Cambodia’s crops by making it hard for Cambodian farmers and fishers to pay back loans they’ve taken out against their assets due to climate change. This is false. Some Cambodian farmers and fishers may be finding it difficult to pay back loans they have taken out to finance production. This is problem for many farmers the world over. However, production of Cambodia’s major crops have increased significantly during the recent period of climate change. As a result, agriculturalists’ financial difficulties are due to factors other than climate change hampering crop production, because it is not.

Jenni Read, the author of the CNBC story, titled “Hit by climate change, farmers in Cambodia are risking everything on microfinance loans,” claims:

Crop failures due to erratic weather and wildfires are leading farmers to take out loans to survive, with their land.

…

The “microfinance” industry — long touted as a way to help poor, rural communities in developing countries — is pushing tens of thousands of farming families into debt traps as they attempt to adapt to a changing climate, according to a report.

Read cites a study produced with funding from the NGO, UK Research and Innovation’s Global Challenges Research Fund, as the basis of her report.

Agriculture is most important source of income in Cambodia’s rural regions, and the third most important sector for the Cambodian economy as a whole, accounting for more than 25 percent of the nation’s GDP.

Like agriculture in neighboring Vietnam and nearby Thailand, Cambodian food production is reliant on seasonal monsoons. Climate Realism previously refuted claims that climate change has undermined crop production in Cambodia, Thailand, and Vietnam by making monsoons more erratic. Since, climate change is not worsening weather trends in the region those countries inhabit it can’t be undercutting food production—and the data confirms, contrary to CNBC’s claim, it isn’t.

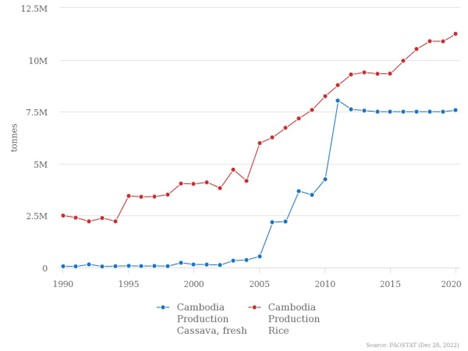

Among Cambodia’s top crops are rice and cassava. Data from the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) demonstrate that between 1990 and 2020, production of each of those crops has broken records for yearly production multiple times. The FAO’s data shows, rice production increased by approximately 350 percent since 1990, and cassava production grew by an amazing 12,527 percent. (see the figure immediately below).

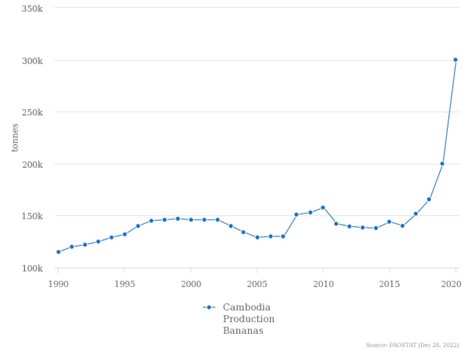

Fruits production is also critical to Cambodia’s agricultural sector, most of which is consumed domestically. Banana is among Cambodia’s top fruit crop and, like rice and cassava, during the most recent 30 years of climate change, banana production has regularly set new records for production. Indeed, banana production in Cambodia increased by just under 161 percent since 1990. (see the figure immediately below).

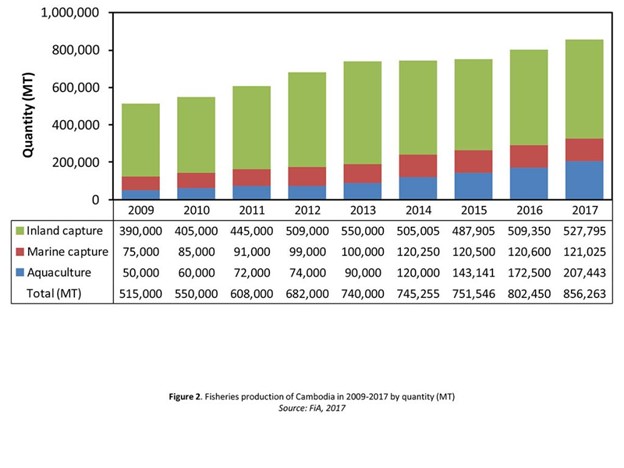

Fish make up the largest percentage of protein in the average Cambodian’s diet. Data shows that fish harvests, both wild and produced via aquaculture, have been increasing. The U.N. FAO doesn’t keep records of sea food production, however, the South Asian Fisheries Development Center has, until recently, for the region. Its data show that between 2009 and 2017, the last year of available data, inland and marine capture of fish, and aquaculture production have all increased substantially, producing an overall increase in fish production topping 66 percent. (See the graphic below).

There is no evidence whatsoever that climate change is undermining Cambodian farmers abilities to pay back existing loans or forcing them to undertake new ones.

The data clearly demonstrate that across the range of Cambodia’s most critical food stuffs, from cereal crops, to root vegetables, to fruits, to fish, production has increased dramatically during the period of recent modest warming. This is fact-based good news CNBC could have reported. Unfortunately, rather than checking the facts, which would have undermined its continuing trend of reporting false climate alarm, CNBC chose to promote the alarmist narrative of impending climate doom, this time as promoted by a climate NGO in the U.K. Bad form, CNBC, bad form.